Part Three

In this final part we list some of the stats and facts including remembering the fallen, and the brave of the police family on the home front in wartime.

Many serving police officers left Devon and Cornwall and went off to join the military at various stages of World War Two. As a reserved occupation, the first called up were those who were already reservists, the rest carried on with their duties. As war progressed the Home Office began calling up the younger men, many of whom had dealt with air raids, firefighting and brave rescues. War Reserves, ‘Specials’ and Auxiliaries were essential to keeping the two counties in order at very trying times.

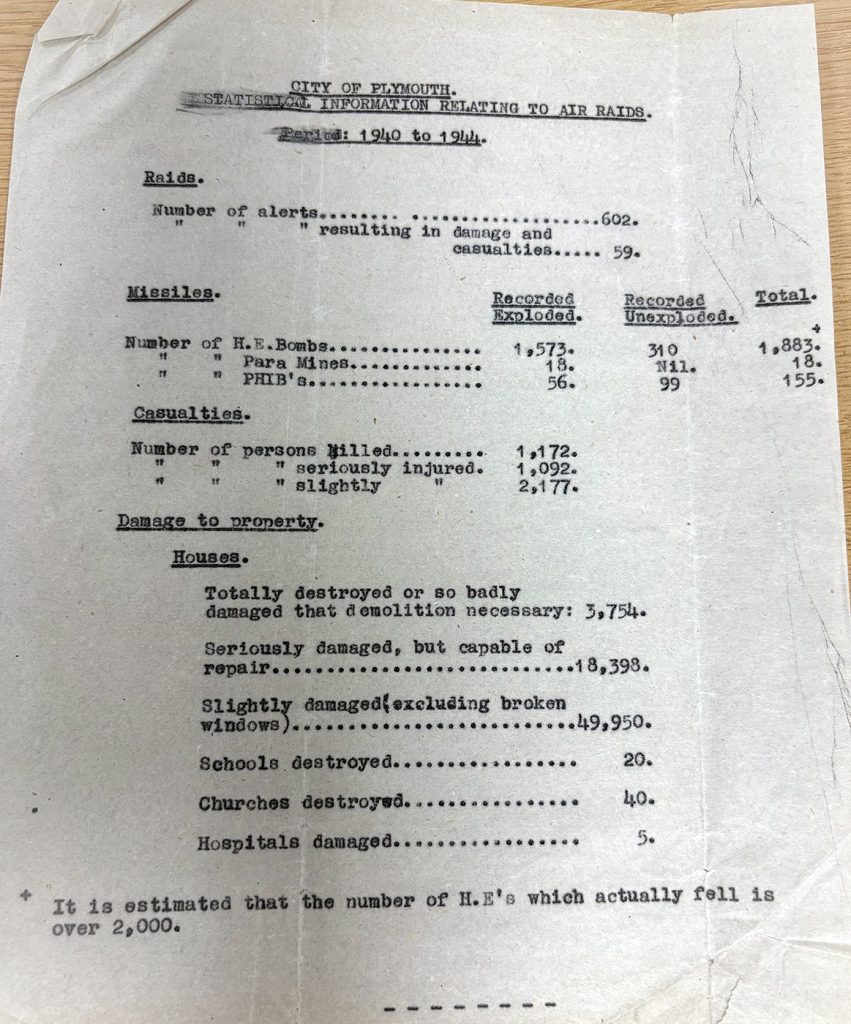

Air Raids and Alerts

The cities of Plymouth and Exeter took the worst of the air raids although bombing and machine gun strafing happened in various areas. Plymouth City’s typed document (Fig 1)shows the number of air raids, casualties etc:

It makes for a sobering read, over 2000 high explosive (HE) bombs dropped, mostly during the Plymouth blitz of 1941.

A comprehensive record was kept known as the ‘Bomb Book’ which is held at The Box in Plymouth: The Box | Blitz 80: The Bomb Book | The Box Plymouth

Exeter City suffered 19 air raids, the worst being the Baedeker raids of 1942 with hundreds of HE and thousands of incendiary bombs released. 268 Exeter people were killed in various raids.

The Fallen on the Home Front

Police officers (including ‘Specials’) killed due to enemy action on the home front 1939 to 1945 are listed below.

Plymouth City Police: Special Constable (SC) Sidney Baker, SC William Beer, PC William Brooks, War Reserve Police Constable (WRPC) Alfred Crosby, Sergeant Edward Gibbs, Special Sergeant Sidney Hannam, SC William Hutchings, WRPC John Balment, WRPC William Cheek, PC William Sandover, WRPC Wilfred Stribley, WRPC Leonard Vickery, PC Kenneth Walters, SC Albert Harris, WRPC Walter White.

Plymouth War Department Constabulary: Sergeant Richard O’Connell.

Plymouth City Police Fire Brigade (a forerunner of the National Fire Service known as ‘Fire Bobbies’): Police Fireman (PF) Joseph Gerretty, PF Walter Northcott.

Exeter City Police: SC Harold Luxton (Fig 2).

Devon Constabulary: SC Francis Allin, SC John Cartwright DSO, SC Samuel Chetham, SC Alfred Ford, SC Ronald Hockin, SC Frederick Pearse, S.Sgt William Rendell, SC Harry Whittaker, WRPC John Worth.

Cornwall Constabulary: No police deaths recorded.

Royal Marines Police Reserve (Devonport Dockyard): RM Police Reserve Constable Alfred Hayward, RM Special Reserve Constable Gerald Rice.

Great Western Railway Police (Plymouth): Railway Constable John Cockwill.

Police Officers who went to war and were killed in action or reported missing in action:

Cornwall Constabulary: PC Thomas Collins (missing in action), PC Daniel Edwards (buried at Assisi War Cemetery, Italy), PC Austin Ware (buried at Banneville-a-la-Campagne War Cemetery, France).

Devon Constabulary: PC Frederick Allen (Buried at Vanciennes Communal Cemetery, France), PC Jack Duncombe (buried at Ranville War Cemetery, France), PC Leslie Leatherland (buried at Newport Cemetery, Wales), PC Maurice Lock (buried at St Anthonis Churchyard, Netherlands), PC Kenneth Mayne (buried at Ford Park Cemetery, Plymouth), PC George Munton (buried at Jonkerbos War Cemetery, Netherlands), PC Ernest Southcott (Munster Heath War Cemetery, Germany), PC Raphael Webber (buried at Ramleh War Cemetery, Israel), PC Ronald Williams (buried at Yokohama British Cemetery, Japan).

Exeter City Police: PC Donald Hawken (buried at Dunkirk Town Cemetery, France), PC Samuel Richards (buried at Reichswald Forest War Cemetery, Germany).

Plymouth City Police: PC Roy Chilcott DFC (buried at Berlin War Cemetery, Berlin), PC Reginald Sandover (buried at Marissel French National Cemetery, France), PC Norman West (buried at Hanover War Cemetery, Germany).

A List of Bravery & Gallantry Awards for Police Officers (including ‘Specials’) on the Home Front.

George Medal: Police Constable Richard Joseph Smale Willis of Plymouth City Police.

His story is recounted here by Anne Corry: Richard Willis, aged 32 had been a Police Constable for 13 years by the time he received his medal in 1944 and lived at 43a Salcombe Rd, Lipson. Sometime during the war he joined the R.A.F., Constable Richard Willis was on duty in every air attack that Plymouth City sustained.

According to the Chief Constable’s report, “On the 12th August 1943, there was a sharp air attack in Plymouth. Bombs first fell at 0046 hours and he “Raiders Passed” was sounded at 0157 hours. When the “Alert sounded Constable Willis was on patrol duty in Union Street. At 0105 hours a high explosive bomb fell on the premises of the Midland Bank, 60 Union Street. Constable Willis heard the explosion and hurried to the scene; saw that very considerable damage had been caused and that the party walls of numbers 68 and 69 were in a precarious condition and liable to fall at any moment. At this time, he was joined by Marian Jaskowski, a Seaman of the American Merchant Navy.

Richard Willis and Marian Jaskowski climbed up to the first floor of 70 Union Street. In answer to their calling out they heard a faint voice coming from no 69. They saw an arm sticking out of the debris.

Between number 69 and 70 was an alleyway. The outside walls of these buildings enclosing the alleyway were in imminent danger of collapse. What to do next?

The two men bridged the gap between the two houses by means of planks. The gap was approximately six to eight feet wide. They then went into the back room of no 69 and found Leonard George Davey, aged 46 years of 16 Hanover Road, Laira. He was seriously injured but was conscious and the two men immediately set about releasing him from the debris.

Not thinking of their own safety, they worked for over an hour until 0230 hours to get Mr Davey released. They finally succeeded in getting him down to the street and into an ambulance. It was just in time, for they hardly had got clear of the spot when a wall collapsed immediately on the scene with masonry falling all around them. Had anyone been there when the wall collapsed it would have meant instant death.

Unfortunately, Mr Davey succumbed to his injuries shortly afterwards in hospital.

While they were rescuing Mr Davey enemy planes were overhead and bombs were still dropping on the City.

On returning from war service Richard returned to Plymouth City Police and served until, 31st September 1960 when he retired as an Inspector.

George Medal: War Reserve Police Constable Victor William Hutchings of Exeter City Police.

Along with Ernest Howard of the Civil Defence, Victor rescued five people trapped in a cellar in Verney Place, Exeter following an air raid in 1942. The people were trapped under a mess of bricks and debris. William and Ernest bravely dealt with fires and smoke to free the trapped residents. Once the people were freed, both men continued on with their duties.

Order of the British Empire: Special Divisional Commandant Cecil Charles Cooper of Plymouth City Police.

Cecil gave valuable assistance during air raids, searching houses for trapped people and salvaging food from bombed and often still burning premises. Mr Cooper endured long duties and difficult conditions demonstrating great courage.

Member of the British Empire: Superintendent Alexander Hawkins of Plymouth City Police.

Alexander played a major role in the police response to the war effort, on constant patrol dealing with air raids and leading rescue work including fire fighting and salvage of goods. Mr Hawkins carried out his duties without regard to his own safety. He retired from police service on 25th February 1945.

Member of the British Empire: Deputy Chief Constable (Chief Superintendent) John Hingston of Plymouth City Police.

John maintained effective control of many important and serious incidents. He displayed great resourcefulness, effort and ability. Mr Hingston shared with his men the full dangers and discomforts, displaying courage and cheerfulness. In 1948 John was awarded the Kings Police and Fire Service Medal for Distinguished Service. He retired in November 1949.

(Fig 3) British Empire Medal for Gallantry: Inspector John Frederick William Lindsey of Plymouth City Police.

During an air raid at City Hospital, Plymouth, children and nurses were trapped beneath burning debris. Mr Lindsey directed rescue operations despite bombs continuing to fall, leading to the rescue of nine children. John had been commended for his attention to duty several times during his career and retired in November 1949.

British Empire Medal for Gallantry: Police Constables William Cecil Marshall, Terence Albert O’Connor, Frederick Samuel Stanley and Special Constable Alfred Henry Dearing of Plymouth City Police.

William, Terence, Frederick and Alfred were all awarded the BEM for their courage during an intensive air raid in 1941. Business premises had been hit and fires were raging, despite this all four men rescued and rendered first aid to many people. All whilst bombs continued dropping and buildings were collapsing. William Marshall retired in July 1958. Terence O’Connor retired as Inspector in January 1966. Frederick Stanley left the police in 1946. Unfortunately, there is no further information about Mr Dearing.

British Empire Medal for Gallantry: Police Constable Victor Charles Cobley of Plymouth City Police

Victor (Fig 4) worked to rescue people trapped in a partly demolished building. He also helped those bombed out of their homes before working to rescue other residents after a house received a direct hit and was on fire. Mr Cobley worked at great speed and exhibited a high standard of conduct throughout. Victor Cobley retired as Chief Inspector from Devon & Cornwall Constabulary on 30th September 1969.

British Empire Medal for Gallantry: Inspector Herbert William Davey Beswick and Police Constable Alan John Tucker Hill of Plymouth City Police

During an air raid and goods depot and ammunition store were on fire. A burning wagon in a shed containing foodstuffs needed to be moved urgently, food was in short supply in the city. Herbert and Alan managed to push the burning wagon away from the shed whilst ammunition exploded around them. Their actions saved the essential food supplies. Herbert Beswick retired as Superintendent in January 1958. Alan Hill enlisted into the RAF in 1942 and stayed on after the war ended.

British Empire Medal for Gallantry: Police Fireman John Francis Cresswell Peace and Police Fire Inspector Arthur William Larson of Plymouth City Police Fire Brigade

An enemy bombing raid caused several fires at the bus depot. Burning oil and exploding petrol tanks made operations very dangerous. With Auxiliary Fireman Edgecombe they took up the most dangerous positions to fight the fires under constant bomb blasts and flying debris. John Peace retired in May 1966 and Arthur Larson retired in 1958.

British Empire Medal for Gallantry: Police Fire Inspector William Thomas Hill of Plymouth City Police Fire Brigade

During an air raid William began fire fighting operations. He along with Chief Drake of Stourport Fire Brigade courageously prevented the fires from spreading and saved valuable property from destruction. In April 1948 William resigned from the police and joined Plymouth Fire Brigade.

British Empire Medal for Gallantry: Inspector Clifford Stroud of Plymouth City Police

Clifford maintained effective control of operations during an air raid. In extremely dangerous conditions he directed the rescue of many persons trapped in debris and burning buildings. Several times Mr Stroud was blown off his feet and severely shaken by bomb blasts but continued on duty. He displayed good leadership despite his exhaustion after many hours on duty. Clifford Stroud retired as Superintendent in May 1956.

British Empire Medal for Gallantry: Police Constable Robert Josiah Steer Eakers of Plymouth City Police

Robert organised rescue parties and entered a collapsing house which resulted in the rescue of five occupants. Prior to that Mr Eakers had carried an elderly woman to safety down two flights of stairs and out of a burning house. Constable Eakers retired in August 1957.

British Empire Medal for Gallantry: Police Constable Daniel Crutchley of Plymouth City Police

Daniel worked through coal gas fumes and debris in a demolished house after an air raid to rescue three men. It took five hours of removing the debris from a limited space despite the danger of further building collapse to get the occupants out alive. Mr Crutchley retired as Inspector in March 1962.

British Empire Medal for Gallantry Bar: Special Inspector Frederick John Cox of Plymouth City Police

The Bar was added as Special Inspector Cox had previously been awarded the B.E.M. Frederick was off duty during a severe air raid, realising the danger the fierce fires posed, he immediately organised firefighting groups to quell the flames. Mr Cox then then led a rescue party and saved two people from a demolished store whilst HE bombs were still falling nearby.

British Empire Medal for Gallantry: Police Constable George Harold Shapter of Plymouth City Police

In 1944 an aircraft had crashed onto a train, it rested upside down on top of paraffin drums the plane’s fuel tanks exploded. George went to the aircraft, and with others pulled one airman out of the flames to safety. He returned to the plane to help the pilot the aircraft exploded causing PC Shapter to suffer burns and other injuries. Mr Shapter retired in 1945.

King’s Commendation for Brave Conduct (a small silver oak leaf): Special Constable John Balsom of Plymouth City Police

John was an original member of the Special Constabulary Mobile Section. This section worked continuously during air raids and SC Balsom won this commendation for his work during 1941.

King’s Commendation for Brave Conduct: Sergeant William John Loram of Plymouth City Police

Wiiliam was awarded for his work during an air raid helping at City Hospital which had received a direct hit by a HE bomb in 1941. Mr Loram retired as Inspector in July 1957.

King’s Commendation for Brave Conduct: Special Inspector George Henry Strathon of Plymouth City Police

During the blitz of March 1941 George (Fig 5) had been off duty but took charge of operations to fight fires in his locality. He gathered a rescue group together saving eight people from their bombed houses whilst HE bombs continued to fall. Mr Strathon had been on duty most of the day and from the time of the raid he continued on duty until 10 am the next day.

King’s Commendation for Brave Conduct: Police Constable Ernest Fraser of Exeter City Police

Ernest was commended for his work during an air raid in Exeter, working through falling masonry to save three people from a shelter at East Avenue in 1942. After an exemplary career Mr Fraser retired as Inspector in July 1957.

The Police in 1945

‘Peace has come again to the world’

The words of Prime Minister Clement Atlee announced the final victory over Japan on 15th August 1945.

The Special Constabulary had proved to be essential in augmenting the regular police force all over Devon and Cornwall. Exeter City invited their ‘Specials’ to take part in the thanksgiving service following VE Day (Fig 6).

Roy Ingleton in his book ‘The Gentlemen at War’ (1994) recounts the observation made in the HM Inspectors Report for the year ended 29th September 1945:

As HM Inspectors we wish to avoid too fulsome expressions of praise for the police service … but we should be doing less than our duty if in this Report we failed to pay tribute to the work of the police as a whole during the war: Virtually the whole of the whole of the younger officers were absent on active service, and many of those left were old for the arduous and uncertain tasks of a police officer, but they have borne their burdens … with their customary faithfulness … The public appreciation of the police has never been greater, the confidence that is placed in the police has never been higher and the relationship between the public and the police service was never better. For this state of affairs all ranks of the service – men and women, regulars and auxiliaries, part-time and whole-time alike – can take credit.

The police officers called to war were returning to their old jobs, and those who had remained at ‘home’ now had to deal with the changes and difficulties of peacetime. There was much adjustment to be made, standing down of those who were waiting to retire, continuing of rationing, and for many in badly bombed areas, no proper home. Married police returning from war back to their home force, found themselves being separated from their wives and families due to the huge shortage of housing. Those who had gained a higher rank in their military service found they were unable to transfer those ranks back into the police, and some chose to re-enlist into military service where possible. However, for those like Victor Cobley that were able to adjust, their war experience meant they were able to achieve early promotion and enjoy a very successful police career.

It has been a a privilege to look at the work of the police in Devon and Cornwall during World War Two, initially to look at VE Day 80 which then evolved into an exhibition and it seemed only right to put the blogs together too. We’ve learned so much and our respect for those who went ‘through it’ during World War Two has increased tenfold.

Thanks to Anne Corry, Mark Rothwell, Peter Hinchliffe, Andrew Veal-Cox, Simon Dell MBE, QCB & Edward Trist (Book: Take Cover), Roger Campion (Book: The Call of Duty), Walter J Hutchings (Book: Out of the Blue) and Roy Ingleton.