In June 2024 those who risked and gave their lives in the world’s largest-ever seaborne invasion were remembered. To commemorate the 80th anniversary of D-Day the Museum of Policing in Devon & Cornwall uncovered some secret and confidential information memos received by the Devon Constabulary at the height of the Second World War.

The top-secret documents, stored in the Museum’s archive, and artefacts preserved in our collection, tell of a time when the communities of Devon and Cornwall rallied round to support the wartime efforts, and how the role of the police across the two counties was seen as crucial in defending our troops and country.

To mark D-Day 80 the Museum shared some little-known information and letters from the Home Office, plus internal communications, found in the records relating to the actions of the police during WWII between 1943 and 1944, as set out and circulated to Devon Constabulary.

Some 156,000 allied troops took part in D-Day, crossing the channel to Normandy on June 6, 1944, going into battle to liberate western Europe from German occupation and ultimately unite with Russian allies at Torgau on the Elbe in May 1945.

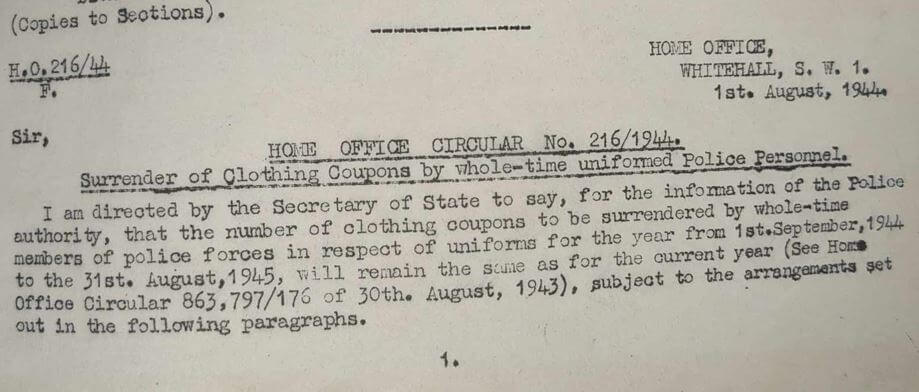

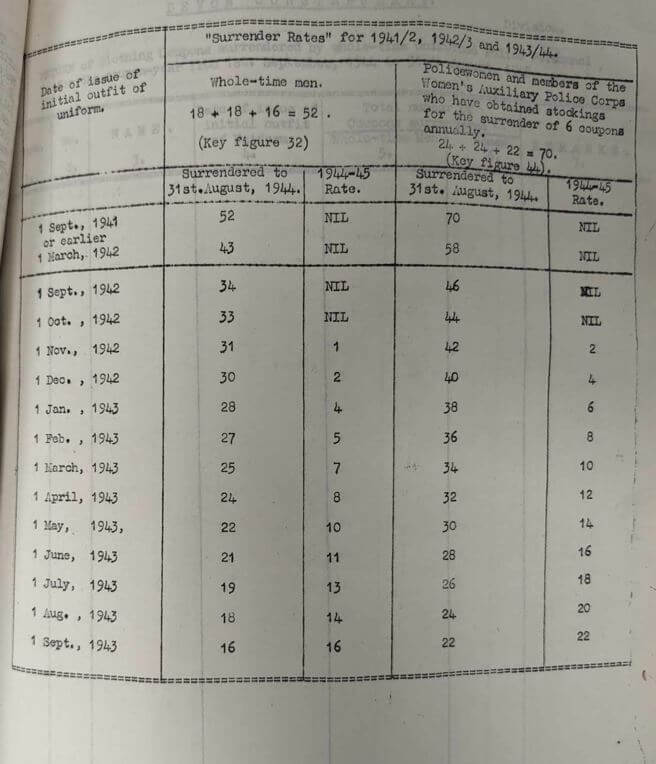

• RATIONING: Harsh rationing rules in August 1944 required police to return some of their clothing coupons.

The Home Office decided whole-time serving police had their uniforms to wear and reduced their allocation of clothing coupons.

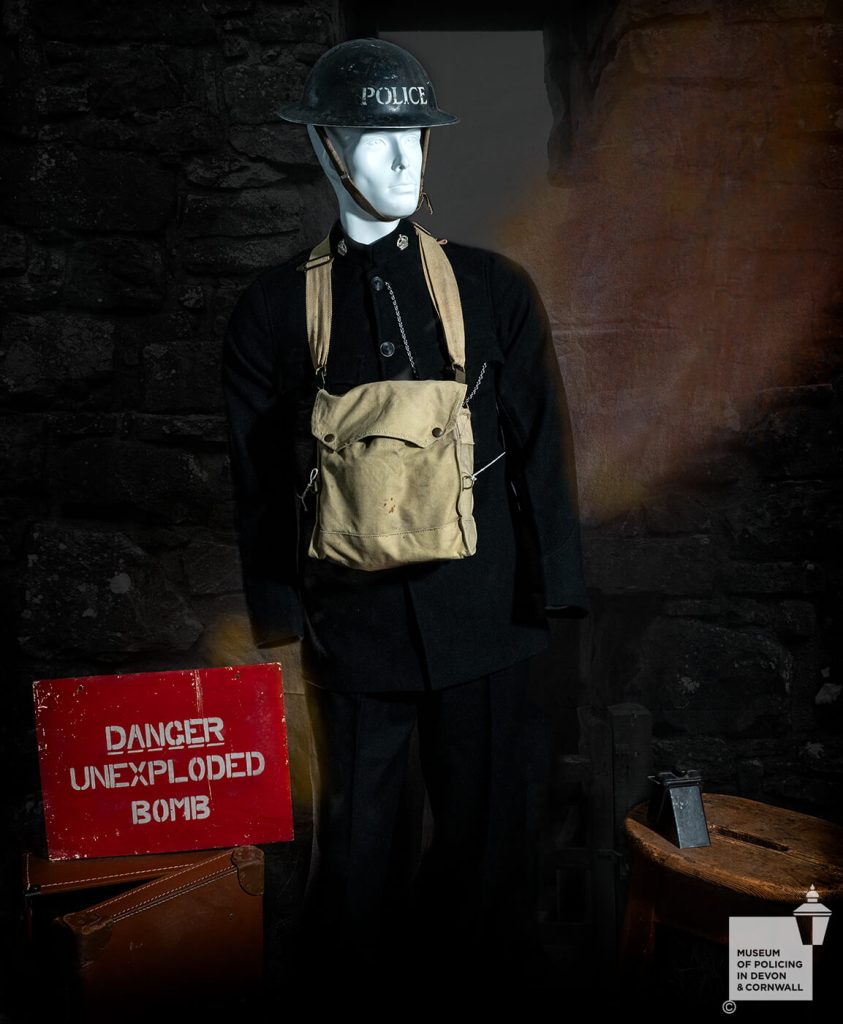

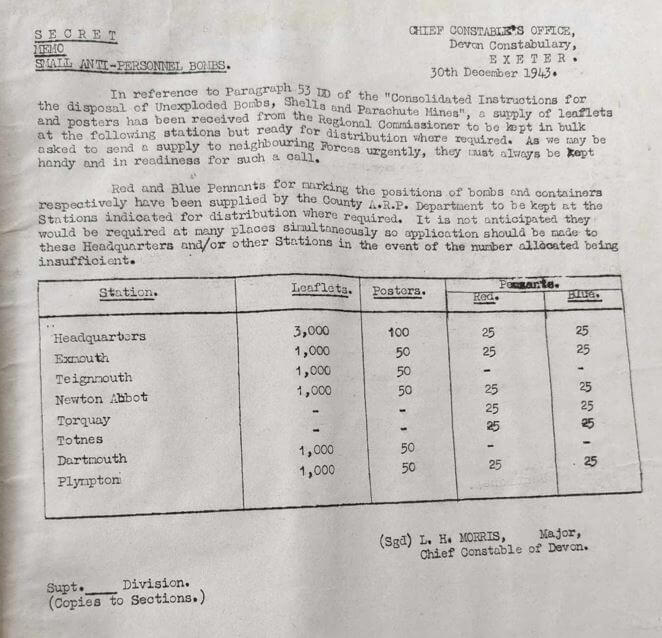

• BOMB INFORMATION: A secret supply of posters and leaflets on how to deal with unexploded bombs were stored at police stations across Devon.

A secret memo sent to the Devon Constabulary Chief Constable’s Office, December 30, 1943, revealed they must ‘be kept handy’.

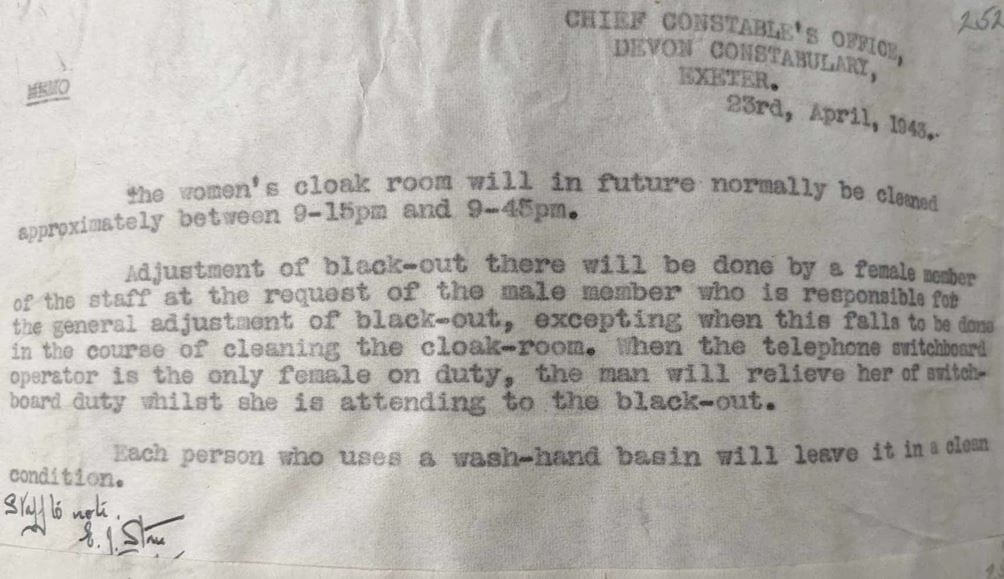

• BLACKOUT AND BASINS: Amid wartime fighting, there was still time to declare hand-wash basins in the women’s cloakroom would be left clean by whoever used them.

And the order included a complicated arrangement of who was allowed into the female-only area during blackout.

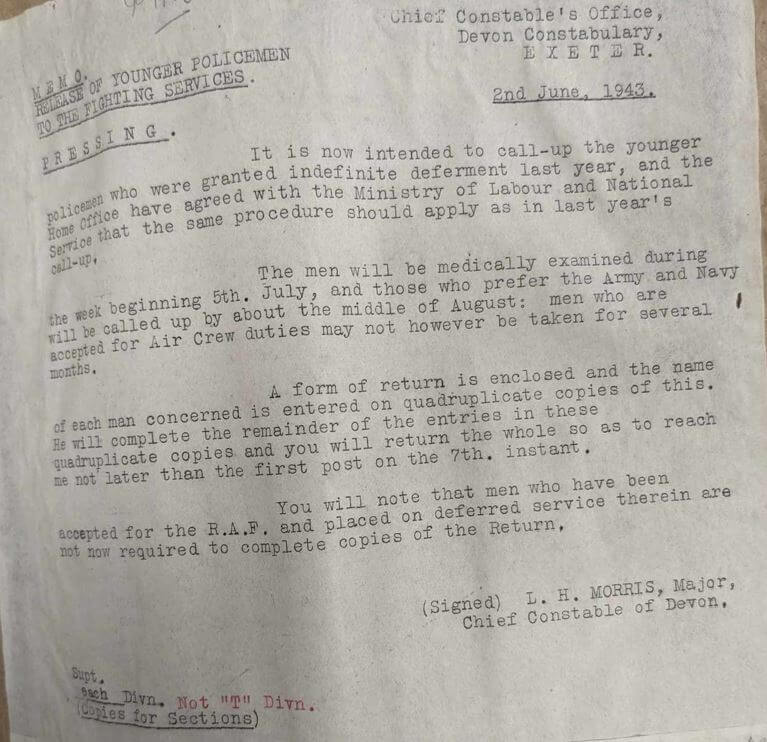

• CALL-UP: A U-turn decision on ‘younger policemen’ opting out of fighting came in June 1943, with a ‘pressing’ memo revealing they would now be called up to serve.

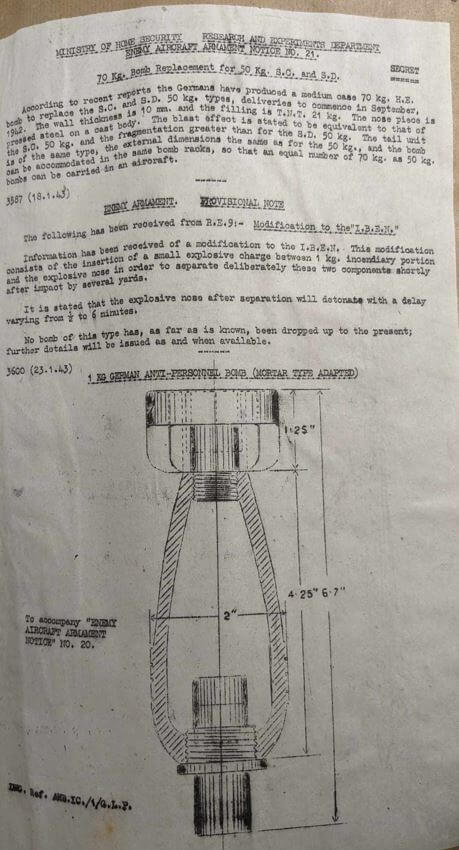

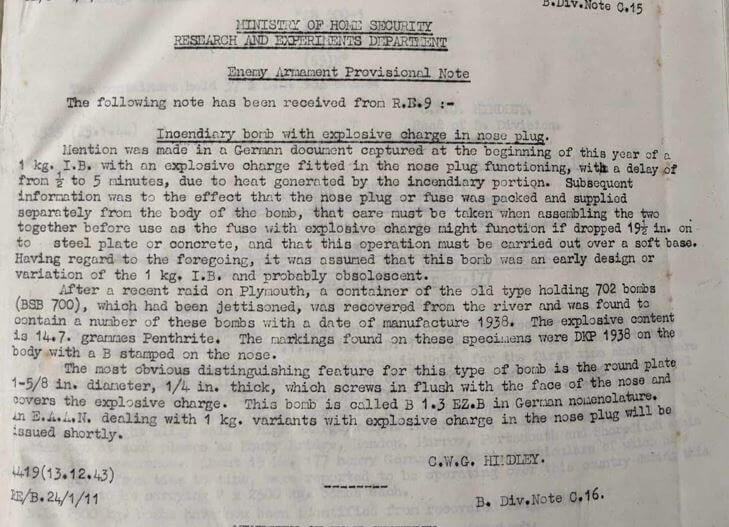

• BOMBS: A hand-drawn diagram of a 1kg German Anti-Personnel Bomb shared in a secret memo warned how the modified explosive was designed to go off at different times with up to a six-minute delay because the nose and body could separate and explode independently of the other.

• BICYCLES: Police using their own bicycle during the war effort received a monthly allowance to pay for its maintenance and upkeep.

But the payment came with a condition, the bike had to be regularly inspected to make sure it was working and safe to use.

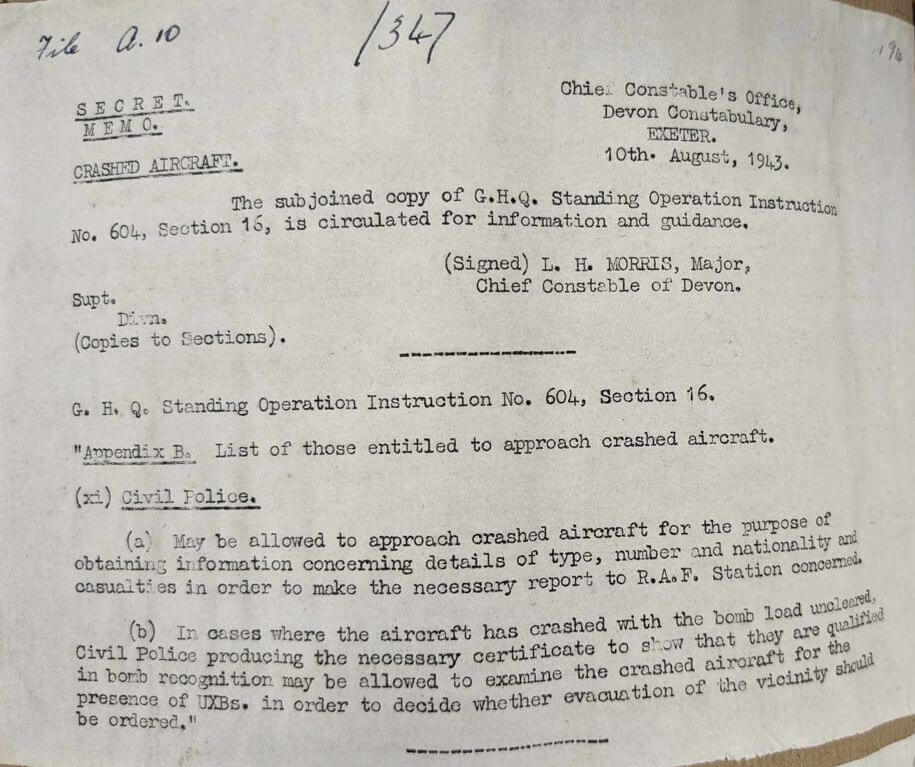

• CRASHED PLANES: Police were allowed to go up close to crashed planes to look for any unexploded bombs onboard to decide if the area should be evacuated – but they had to show a certificate first to prove they were qualified to identify bombs.

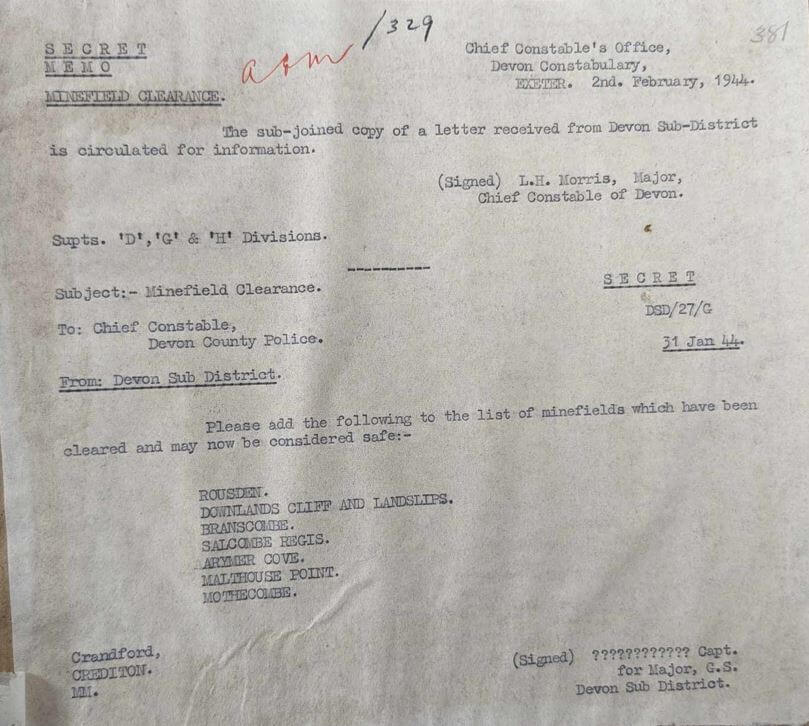

• MINEFIELDS: When minefields were cleared in Branscombe and Salcombe Regis, both in East Devon, and Malthouse Point and Mothecombe, in South Devon, Devon Constabulary received a secret memo to say the areas were ‘now considered safe’.

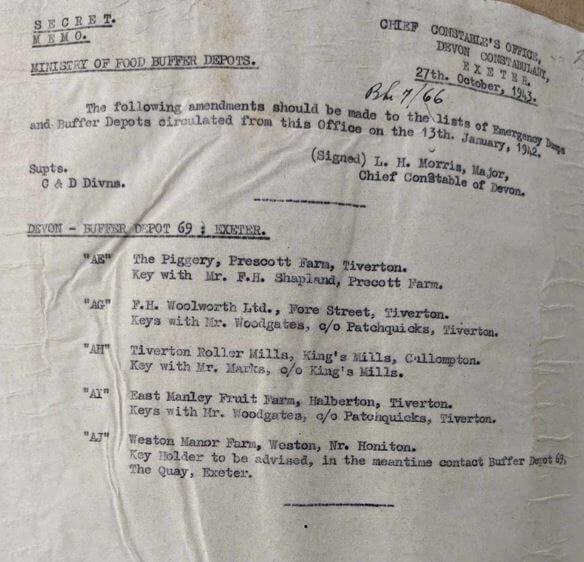

• FOOD: Food was stockpiled in ‘Buffer Depots’ throughout Devon – warehouses and emergency stores housed dry food and grain.

A secret memo received in October 1943 listed farms and a piggery in Tiverton, Cullompton and Honiton.

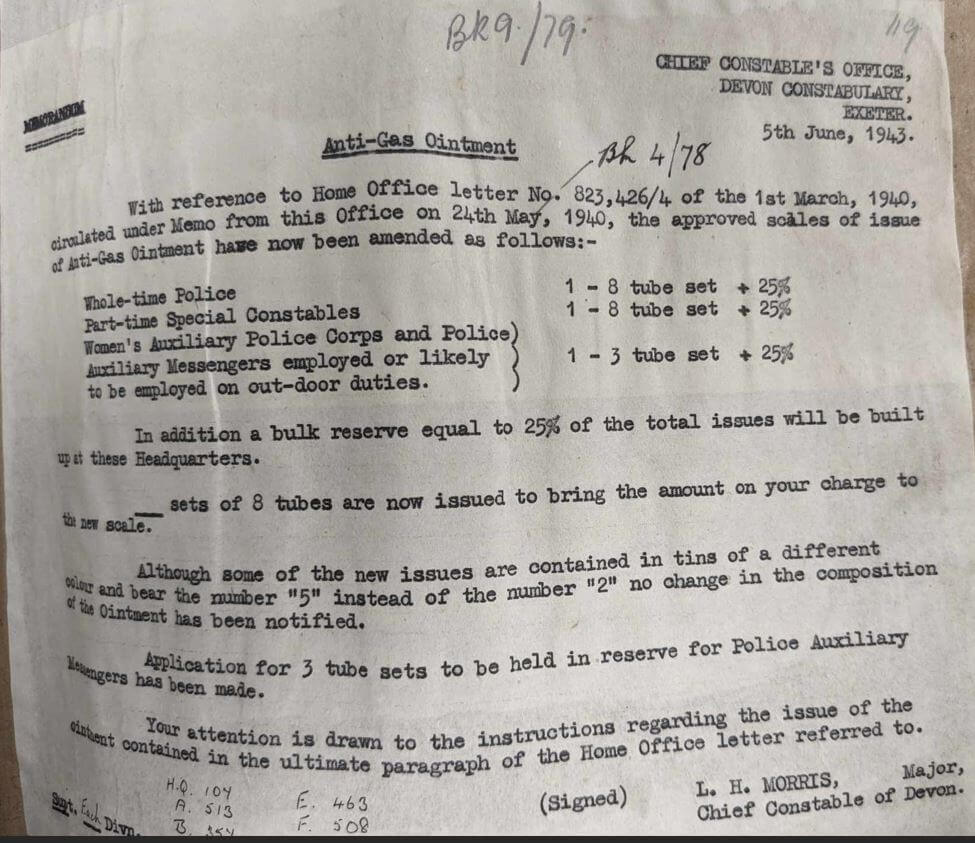

• OINTMENT: Some six months after war broke out the Home Office approved extra tubes of anti-gas ointment for police.

Whole-time Police and part-time Special Constables were allowed up to eight tubes each; Women’s Auxiliary Police Corps and Police Auxiliary Messengers, were allowed up to three tubes each – but only if they were employed on outdoor duties.

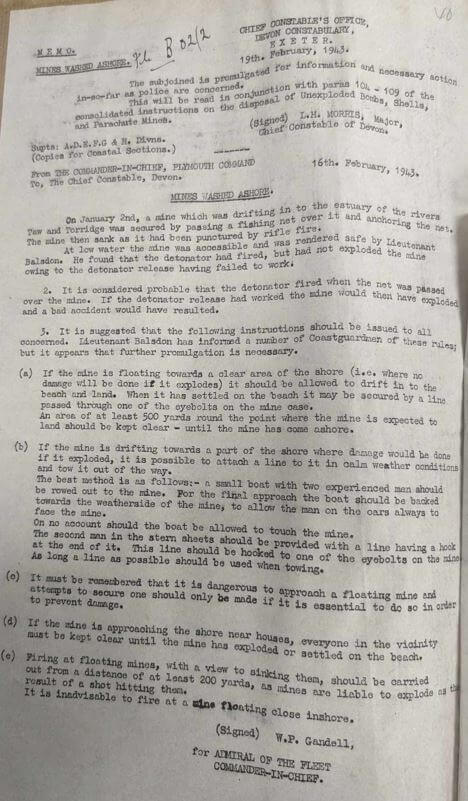

• MINES: A fishing net stopped a live mine from drifting in the water towards the estuary between the rivers Taw and Torridge in January 1943, before it was shot at, and sank.

The Royal Navy said it was ‘probable’ the detonator had fired when the net was passed over the mine, but it had failed to explode, preventing a bad accident.

New rules for dealing with floating mines included towing it away. The best method was a small boat rowed by two experienced men. The boat rower had to ‘always’ face the mine!

‘On no account should the boat be allowed to touch the mine’, the rules warned.

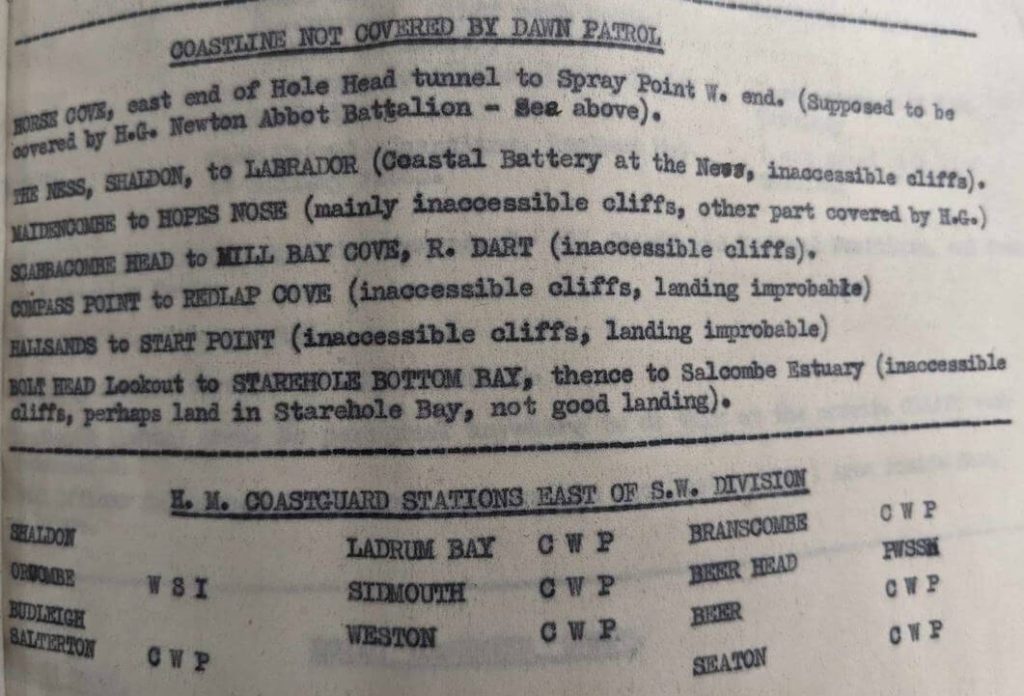

• PATROLS: Parts of Devon coastline went uncovered by dawn patrols because it was decided the cliffs were ‘inaccessible’ and finding areas to land the enemy would have been unlikely.

Areas of coastline the memo included were Dawlish, Shaldon, Dartmouth, Kingsbridge and Salcombe.

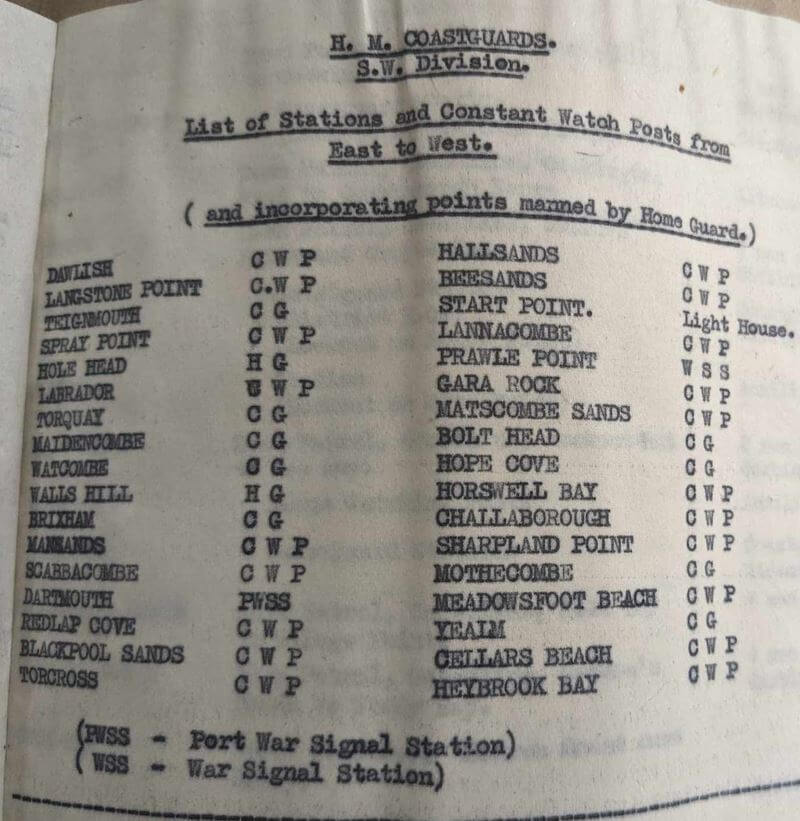

Constant watch posts, some with signal stations, were set up across Devon.

A comprehensive list included points operated by the Home Guard.

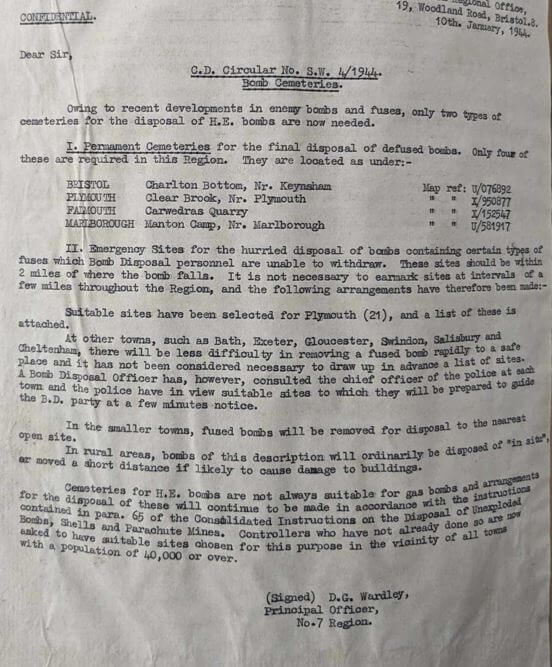

• BOMB DISPOSAL: A confidential memo revealed how three bomb cemeteries had been set up across Devon and Cornwall to dispose of the region’s diffused high explosive (HE) bombs.

The permanent sites were the village of Clearbrook, near Plymouth, Manton Camp near Marlborough, both in Devon, and Carwedras Quarry, in Falmouth, Cornwall. Another was in Bristol.

Towns with more than 40,000 people had to have their own sites set up for the disposal of gas bombs.

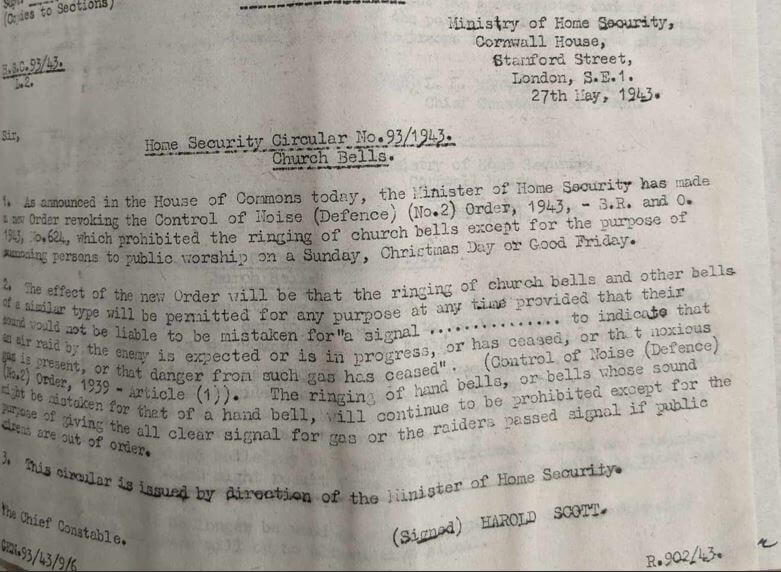

• BELLS: A ban on bellringing was ruled by Parliament at the end of May 1943 in case the sound was mistaken for a signal.

Church bells could only be rung for Sunday worship, Easter and Christmas Days.

The fear was the bells could be taken as a sign the enemy was approaching, or to warn of a gas attack.

And the ban included hand bells unless the warning sirens were broken. Then they could be used to give the all-clear.

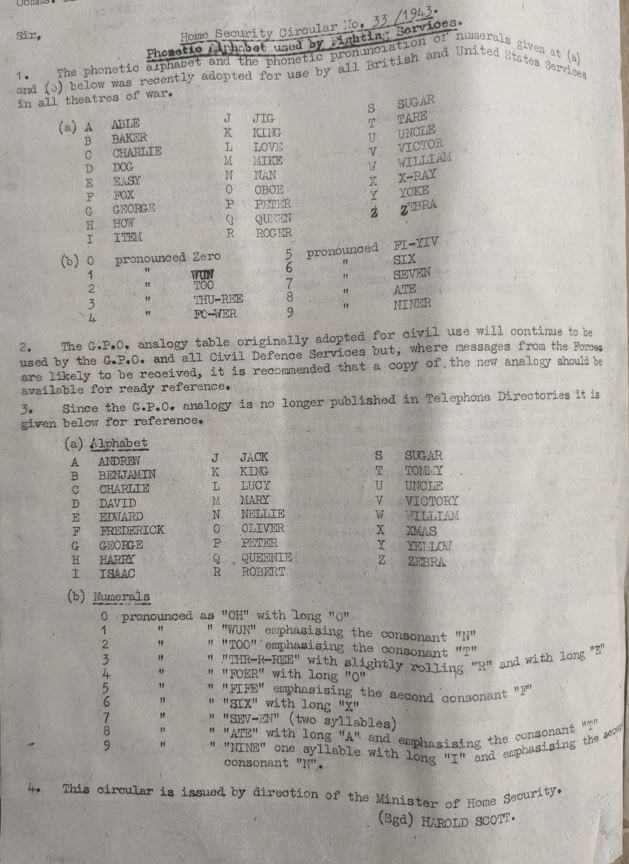

• ALPHABET: The British and United States Services agreed to use the same phonetic alphabet and pronunciation of numbers amid any war or conflict.

Numbers had to be said in a specific way, and a circular set out how they should sound.

The number four had to be pronounced fo-wer, five became fi-yiv, while nine was emphasised as niner.

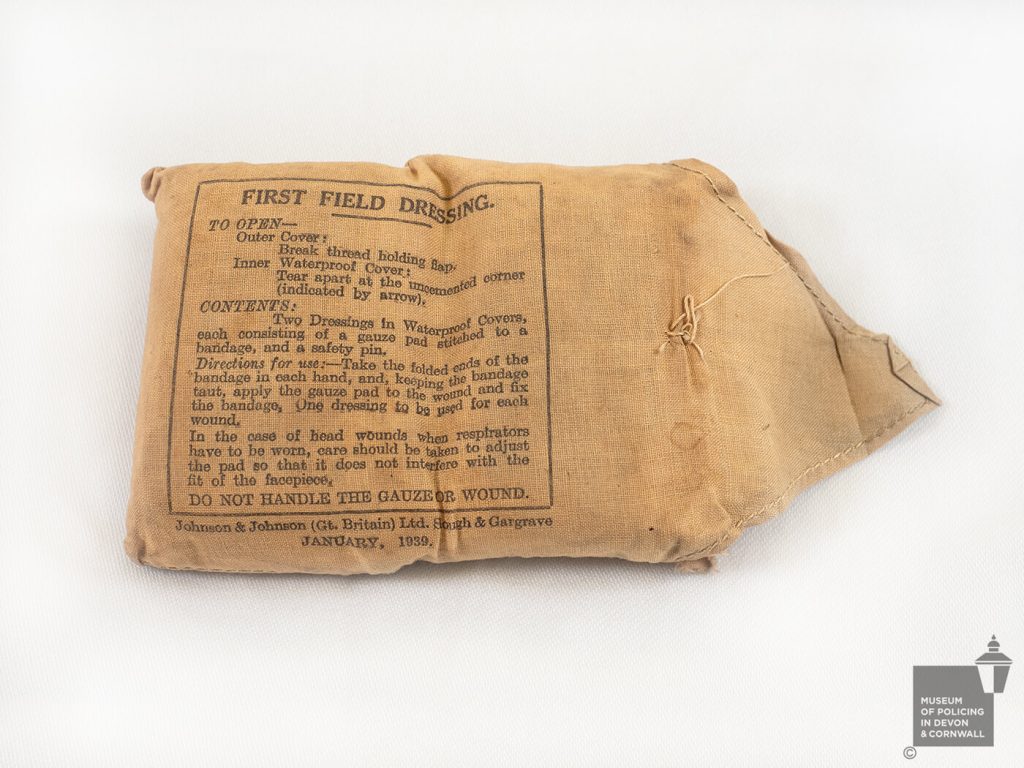

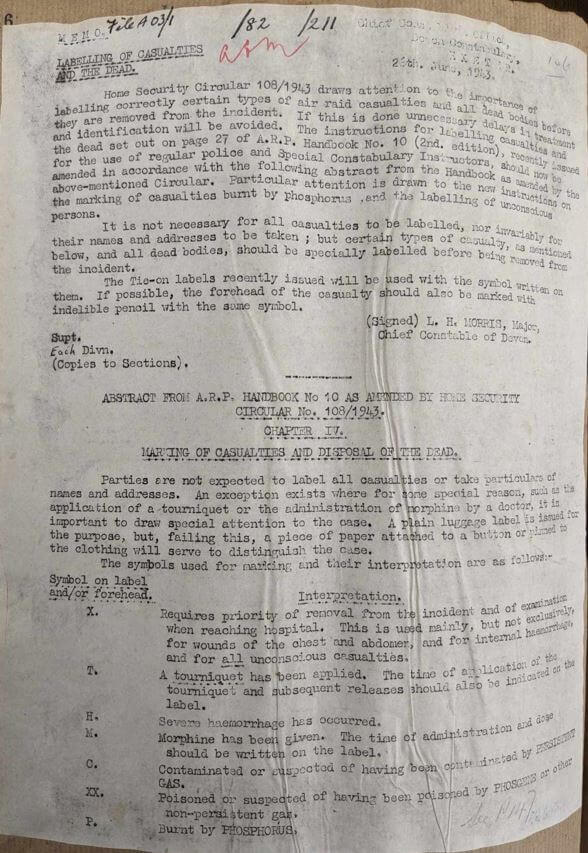

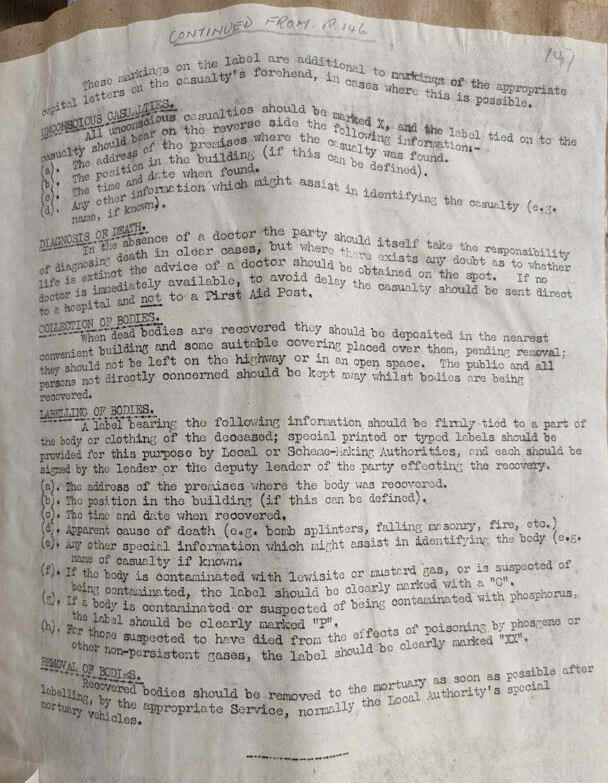

• SYMBOLS: Dead bodies and casualties had symbols drawn on their forehead to help medics or the morgue.

Plain luggage labels attached to some casualties, and all dead bodies, were marked with X, T, H, M, C, XX, or P, depending on the cause of death or injury.

‘If possible, the forehead of the casualty should also be marked with indelible pencil with the same symbol’, said a memo received in June 1943 by the Devon Constabulary.

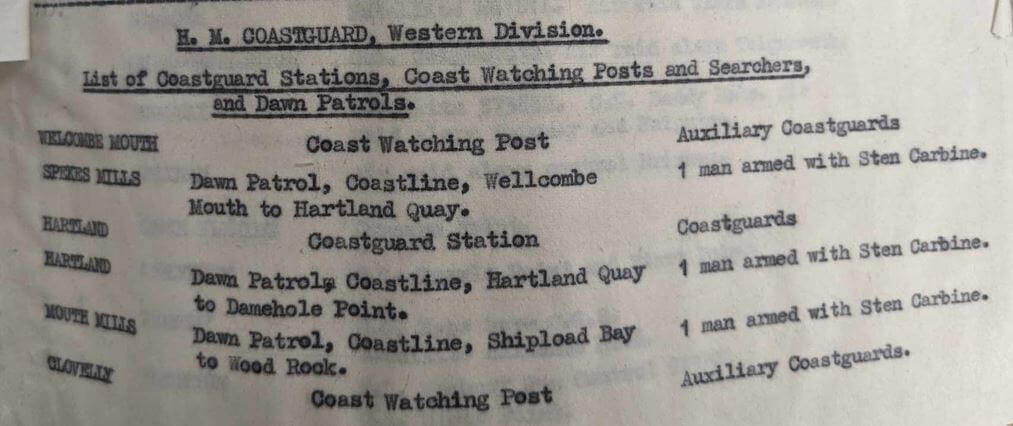

• PATROLS: Auxiliary coastguards carrying rifles were stationed at multiple coast-watching posts in North Devon.

A man ‘armed with a Sten Carbine’ was put on coastline dawn patrols at Wellcombe Mouth to Hartland Quay; Hartland Quay to Damehole Point; Shipload Bay to Wood Rock.

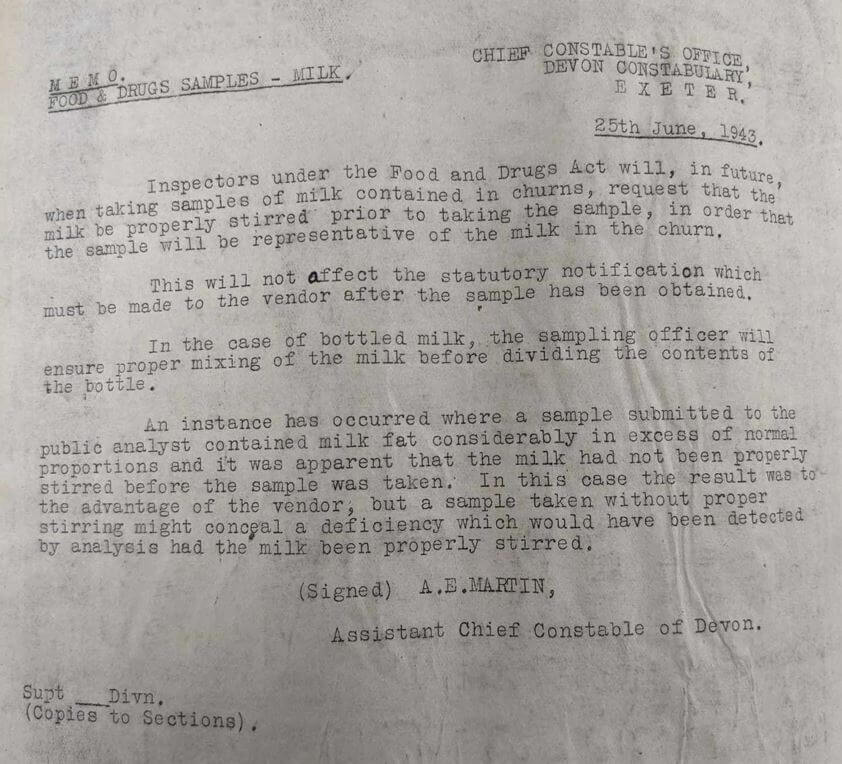

• MILK: A problem with unstirred milk arose in June 1943, prompting the Acting Chief Constable of Devon to step in and order the sampling officer to properly mix the liquid before it was bottled for testing.

Concerns were raised that a churn of farm milk for public rations had been found to contain extra fat because it had not been correctly stirred, which could hide deficiencies.

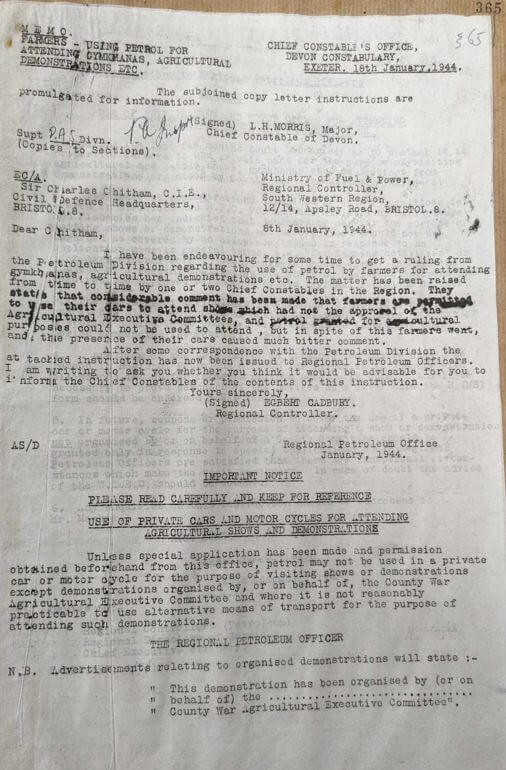

• PETROL AND FARMERS: Devon’s farmers were in 1944 banned from using their own cars or motorcycles to go to agricultural events, shows and gymkhanas because the presence of their vehicles ‘caused much bitter comment’ amid petrol rationing.

A memo from the Regional Petroleum Officer to Devon Constabulary said farmers could only use their own vehicles if they were travelling to an official war effort demonstration, and only as a last resort.

Lorries in convoy spent weeks transporting fuel from mid to south Devon, carrying 40-gallon drums of petrol needed for advancing troops, which were stacked high in Brixham harbour.

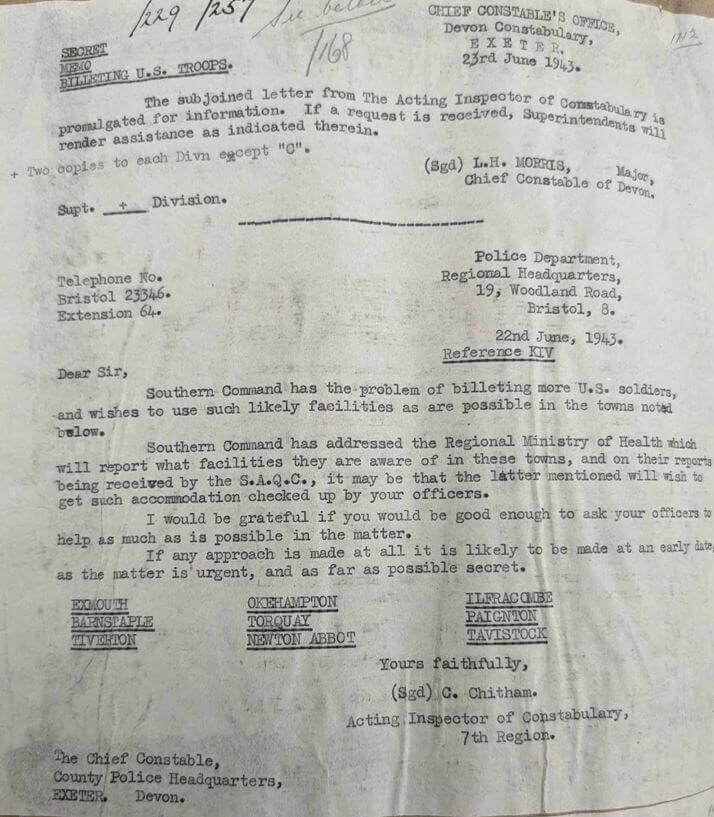

• USA TROOPS: A secret memo revealed more accommodation was needed in towns across Devon to station extra American soldiers.

Devon police were urged to ‘help as much as possible’ to find private lodgings for the troops because the situation was ‘urgent’, although anyone making local enquiries was urged to be discreet.

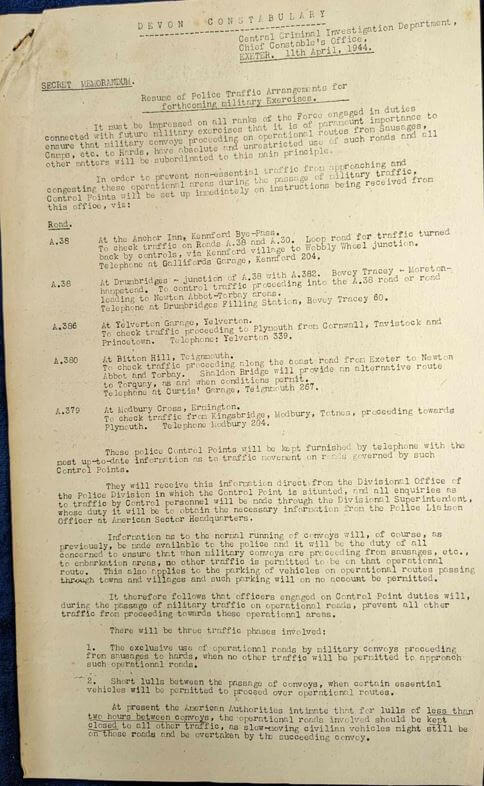

• ROADS: Exeter City Police staffed traffic posts in a bid to check passing vehicles and divert them away from operational areas, now off-limits to the public. A policeman was stationed on every junction along the main roads. In Cornwall, the cover came from the Lancashire Constabulary.

• VEHICLES AND SIGNS: Civilian vehicles were banned from almost every main road in Devon and Cornwall, to free the highways for military convoys readying troops and equipment for Normandy. All road signs were removed in 1940 and were not replaced, to confuse the enemy.

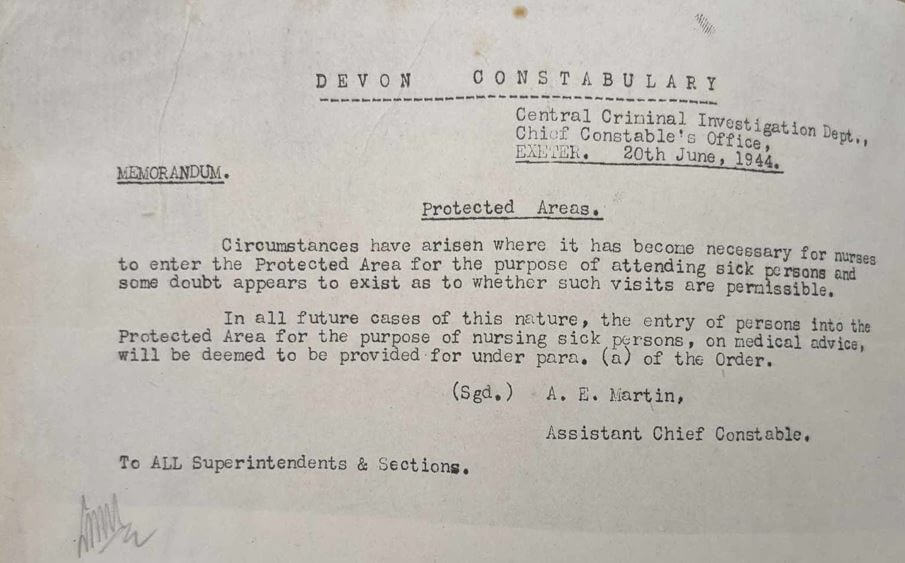

• ZONES: The Government ordered a ‘restricted zone’ in 1944, banning anyone unauthorised from entering a 10-mile stretch of coast, starting at the shore to inland. This included the entire length of the South Coast facing Europe, from Norfolk to Land’s End, in Cornwall.

There was a ban within the zone on having camera, telescope, or binoculars in a public place, unless authorised.

Nurses were allowed into Devon’s protected areas to attend to the sick and give medical advice, but only after the Chief Constable’s Office bent the rules and authorised access, saying ‘some doubt appears to exist as to whether such visits are permissible’.

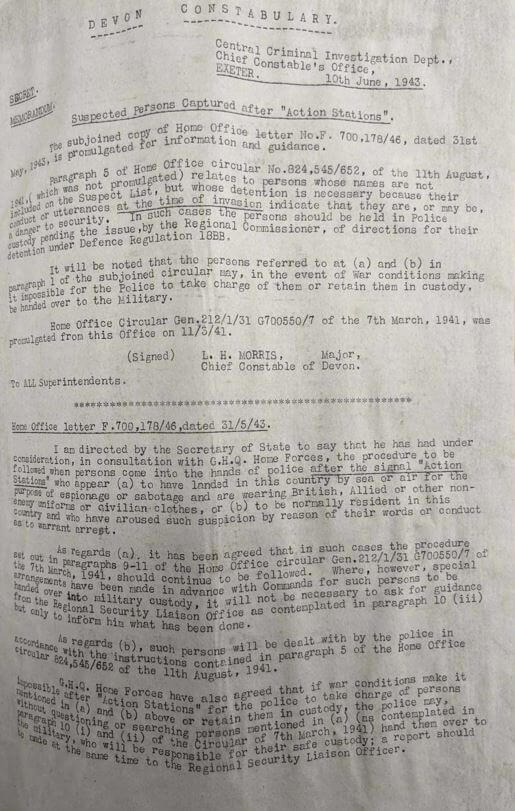

• ARRESTS: Devon Constabulary police were given powers to search, arrest and lock up anyone acting or speaking suspiciously thought to pose a danger to security.

A secret memo revealed police could hand them over to the military if war conditions made it impossible to safely detain the person.

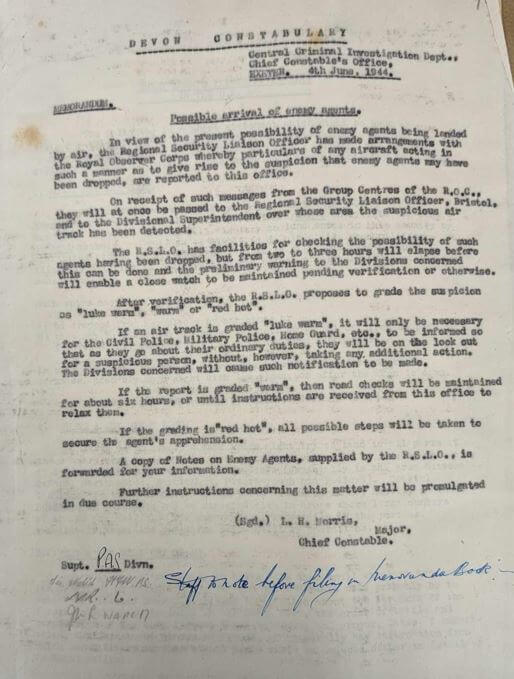

• CODE: Code words ‘lukewarm, warm and red hot’ were used to grade any potential suspicion of ‘enemy agents’ dropped over Devon by air.

Any action carried out depended on the temperature given – setting up roadblocks for a ‘warm’ command and doing everything necessary to stop the enemy agent amid a ‘red hot’ instruction.

• STOCKINGS: Police records dating from 1941 to 1944 show the number of Policewomen and Women’s Auxiliary Police Corps who ‘surrendered’ six clothing coupons each year for their stockings.

All 70 women registered in 1941 swapped their clothing coupons for nylons. The number exchanging coupons for stockings fell as the war went on.

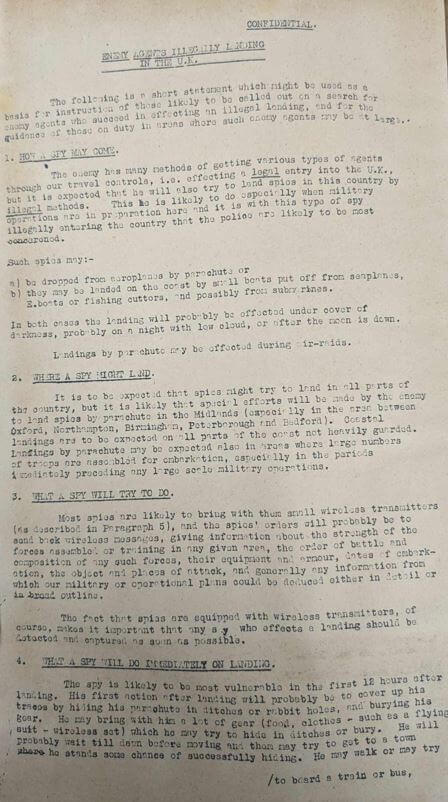

• SPIES: A confidential memo to Devon’s police on all-things espionage detailed how a spy might come into the UK, where one might land, what they would try and do.

Devon Police were warned the spy might try to hide or bury his parachute, food, flying suit and equipment down rabbit holes and in ditches.

And they were told to expect him to get the bus or walk to a town, where he had a better chance of hiding.

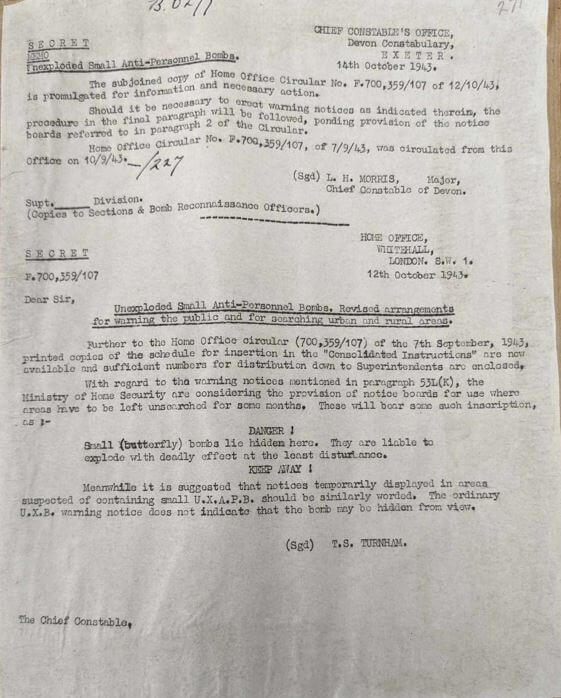

• BUTTERFLY BOMBS: A secret memo sent to Devon police in 1943 revealed plans to put up warning signs in urban and rural areas where small bombs were known to have been dropped and remained unexploded.

The signs, headed with Danger! were expected to say ‘small butterfly bombs lay hidden here. They are liable to explode with deadly effect at the least disturbance’, signing off ‘Keep Away!’.

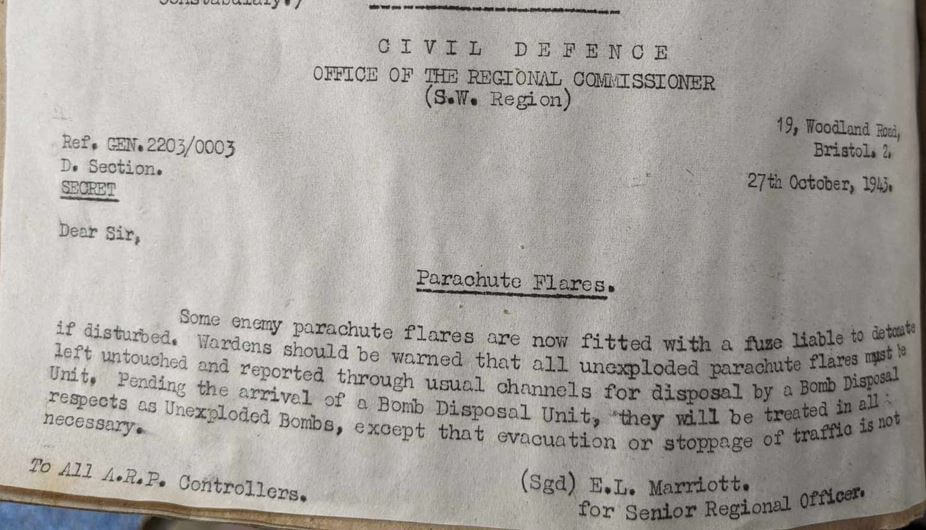

• FLARES: Enemy parachute flares were treated in the same way as unexploded bombs after it was found some had been fitted with a fuse ‘liable to detonate if disturbed’.

A secret memo to police in 1943 warned they must be ‘left untouched’ and detonated by the Bomb Disposal Unit.

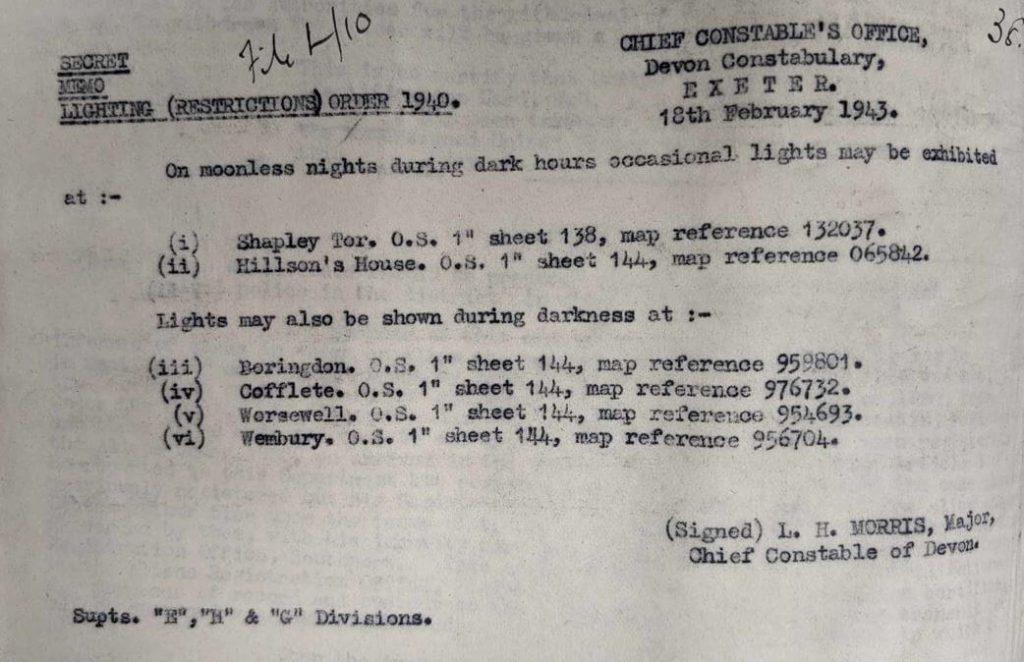

• BLACKOUT: Blackout regulations banning street, window and car lights were enforced at the start of the war.

But a secret memo about lighting sent to Devon Constabulary identified specific high points on Dartmoor and coastal areas, where ‘on moonless nights during dark hours occasional lights may be exhibited’.

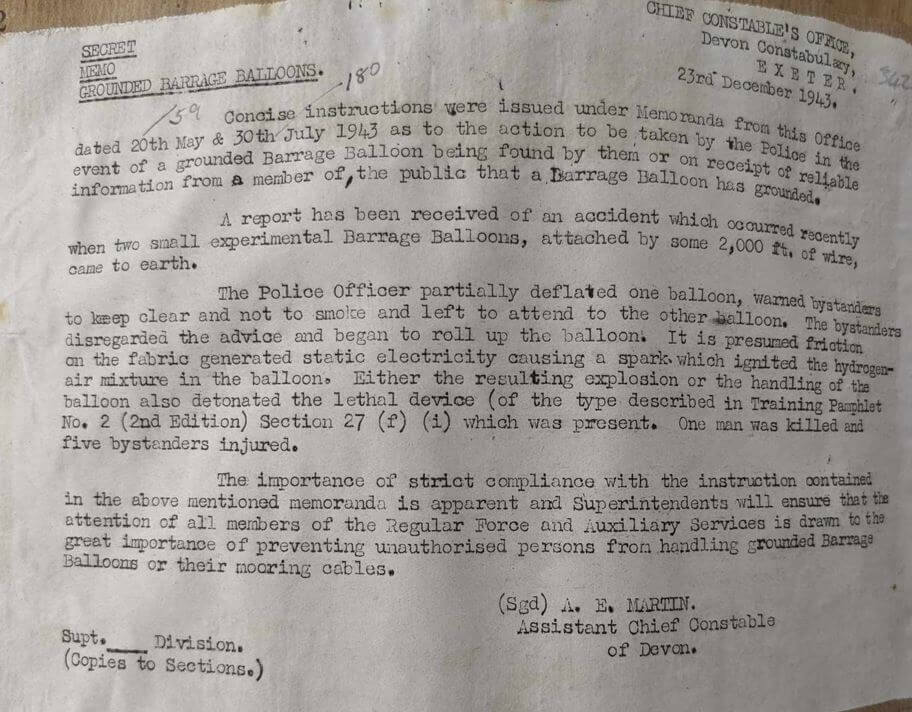

• BARRAGE BALLONS: Days before Christmas 1943, a secret memo to Devon Constabulary told of how a man was killed and five onlookers injured when they ignored a police officer’s warning to stay away from a ‘small experimental barrage balloon’ which was attached to 2,000ft of wire, but fell to the ground.

Despite the police warning to stay away and not smoke near the grounded barrage balloon, after watching the officer partially deflate the object, the small crowd started to roll it up.

Static electricity from the rolling resulted in a spark, which set fire to the barrage balloon’s hydrogen air mixture. The ‘lethal device’ detonated and exploded with fatal consequences.

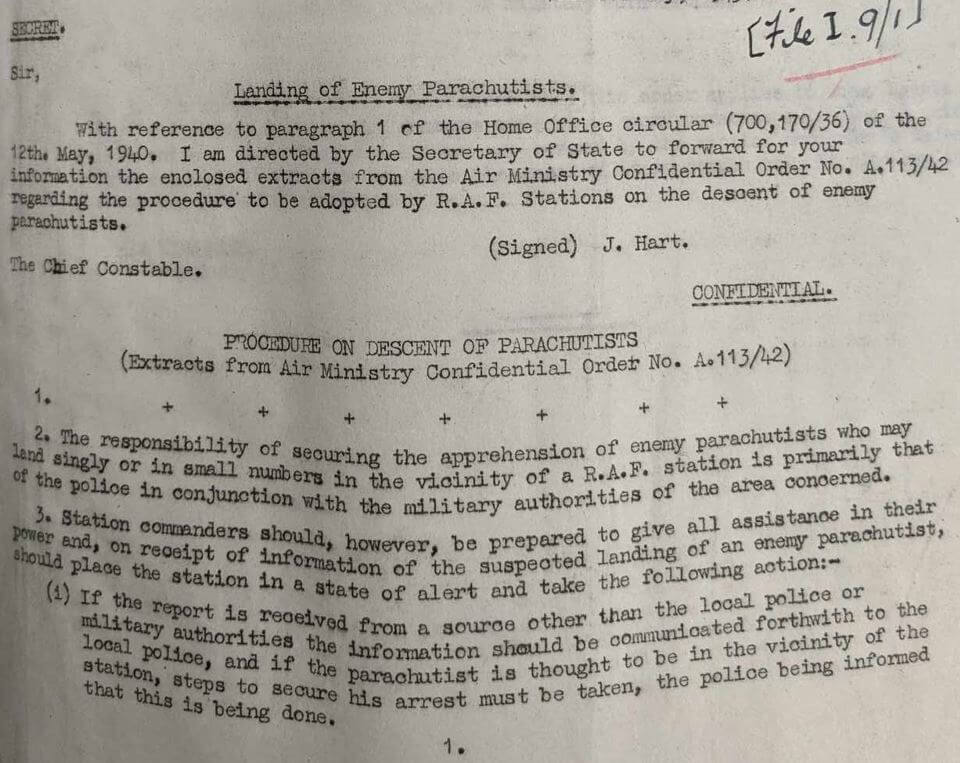

• PARACHUTISTS: Enemy parachutists landing near RAF stations in Devon were arrested by military authorities, who alerted local police, a secret and confidential memo in Devon Constabulary files showed.