The Blitz

Heavy air raids plagued Plymouth from March to April in 1941 flattening large areas of the city. The orange glow of the blazing city could be seen for miles. Huge fires raged all around, people were trapped amongst rubble and burning buildings. Plymouth City Police were responsible for the fire service, however, calling in assistance from other areas including Saltash caused Chief Constable Lowe (also the Chief Fire Officer) great frustration. The Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS) crews from outside of Plymouth came to the aid of the stricken city only to find they were unable connect hoses to hydrants not already damaged by bombing. Fire hydrants were not standardised at the time despite numerous sensible requests from the Chief to do so, this left AFS crews and police having to watch helplessly as buildings burned. As a result of this, adaptors were eventually provided for crews to collect on arrival in Plymouth as the air raids continued. Mutual aid from Devon and Cornwall Constabularies (Fig 1) and from Exeter City were essential in coping with the devastation suffered.

Training

Many people do not realise that some police officers were armed during wartime. A number of regular policemen and war reserve constables were issued pistols and told to guard the docks as well as the Cattedown and Prince Rock industrial estates in Plymouth. These sites were declared prohibited areas; armed officers conducted patrols around them and checked the passes of those who worked there. For those unfamiliar with firearms, elementary weapons training was provided by PC Jack Downs, an ex-marine, at Mutley Barracks assisted by PC Roy Jewell. Roy’s prior military service was useful, and he assisted Jack in how to use the weapons. Roy told how one constable, whose revolver had become jammed, turned around with it still loaded and asked for help, muscle memory compelled Roy to dive for cover!

The training of the police, air raid precautions, civil defence, ambulance and other related organisations proved critical. However, with the ferocity of the air attacks in Plymouth, there were difficulties gaining entry into burning buildings, not enough ambulances were available, and telephone communications were knocked out by the bombing of the Guildhall. The Royal Navy stepped in to assist with staffed ambulances for the injured, and use of motorcycles to aid communications.

Anne Corry has carried out extensive research on Plymouth in wartime; one of her stories of police bravery is reproduced here:

Police Constable 32-year-old Daniel Crutchley and Special Constable 46-year-old Percy Thomas Gollop, a master butcher, on hearing that people were trapped inside a basement of 3 large double-fronted demolished houses which had received direct hits on 21st March 1941 in Devonport, risked their lives and ignoring their own safety, dug with their hands for several hours with gas and bombs dropping over them to rescue those inside.

On arriving at the scene Constable Crutchley took charge of the incident and found a number of persons trapped in the basement of one of the houses. A large quantity of masonry and loose timber was immediately over the spot at which it was necessary to commence rescue work, and this was likely to collapse at any moment. Regardless of this danger, and the presence of coal gas, Daniel started digging and continued for several hours by hand-picking the debris. He was assisted by a Warden named Pethick and Special Constable Gollop. The work was made more difficult owing to the very limited space available which only permitted two men to dig at a time. Crutchley was actively assisted during the whole period by Pethick and Gollop, these men taking turns and relieving each other.

After five hours 3 men were rescued alive, and the bodies of two women recovered. A Rescue Party arrived as Crutchley was freeing the three men. Three other bodies were later recovered from the ruins. For one brief period alone Crutchley ceased his efforts, and this was when he was partly overcome through the effect of gas. Crutchley continued ceaselessly and untiringly for a further five hours in rescue work and the removal of other bodies. Chiefly through the untiring efforts, courage and initiative of this Constable the three persons referred to were rescued alive.

When interviewed by the newspaper Daniel (Fig 3) said, “I have done my job as any other man would have done had he been in my position on that night.”

On the same night Plymouth City Hospital at Greenbank was hit. Anne Corry’s research on this tragic incident is reproduced here and despite the bravery of those involved, it is distressing to read:

Plymouth City Hospital was hit by a high explosive bomb on 20th March 1941 Policemen John Down, John Lindsey and William Loram rescued nine children.

On the 26 July 1941, Western Morning News reported that Inspector John Lindsey, directed rescue operations after the City Hospital had been hit by a high-explosive bomb. Children and nurses were trapped and the debris caught fire, but under the inspector’s brave leadership the police rescued nine children. They, along with Dr Alison Jean McNairn and Nurses Veronica Agnes Clancy, Gwendoline Jane Edwards, Kathleen Margery Giles, Winifred Maud Yearling received awards. Inspector John Frederick William Lindsey, 46 years, was living at 20 Edgecumbe Park Road, Peverell and had been with Plymouth City Police for 21 years. Police Sergeant John James Down, 35 years was living at 50 Rosebery Avenue. He had been with the police for 9 years and Police Sergeant William John Loram, 35 years and was living at 29 Channel Park Avenue, Laira. He joined Plymouth City Police in 1927 and was promoted to Sergeant in 1939. He was married and father to a little boy.

Report by Chief Constable, G.S. Lowe: “On the night of the 20th March 1941, during an intensive air-raid, the City Hospital, Plymouth, was struck by four heavy high-explosive bombs which demolished a Children’s ward. A number of children and nurses were trapped beneath the debris. Under the direction of Inspector Lindsey and Sergeant Loram rescue operations were carried out at once, and by the time the Rescue Party arrived the Police had succeeded in finding among the ruins nine children still alive. In addition, a number of bodies were recovered. During these operations debris caught fire and dense overpowering smoke and fumes made rescue still more difficult. Falling masonry added to the difficulties. The standard set by the police was high, and this was in a large measure due to the leadership shown by the Inspector who maintained complete control of the situation under exacting circumstances.”

Report by Superintendent, H.B. Hawkins: “On the night of the 20th March 1941, during the intensive air-raid on the City, four high explosive bombs struck the children’s ward and the maternity ward in the City Hospital. The children’s ward was demolished resulting in a number of children and nurses being trapped and the maternity ward was extensively damaged. This building is in close proximity to Police Headquarters and Inspector Lindsey was detailed to take charge of Police personnel and was on the scene within a few minutes of the actual report to the Police. I visited the City Hospital a short time afterwards to ascertain the exact position. Inspector Lindsey was directing operations with great calmness and by his own example inspired the men present in the rescue work. At the time high-explosive bombs were falling in the district and fire broke out among the debris giving off strong heavy fumes from burning rubber and smouldering timber. At times the rescuers had to be dragged away from the fumes to recover before resuming the rescue work.

Whilst this was in progress Inspector Lindsey showed calm courage and devotion to duty to duty and by his complete grip of the situation many trapped children and nurses were rescued. His conduct was of the highest tradition and set a fine example to the men working under him. He was ably assisted by Sergeant Loram and Constable Down was outstanding among the other ranks. At considerable risk from falling debris Sergeant Loram and Constable Down did fine work and set an example worthy of the traditions of the Police Force.” Report by P.S. No. 35 W.A. McConnach: “On the 3rd April 1941, I interviewed Dr Larks, Medical Superintendent at the Plymouth City Hospital, in connection with the incidents at that hospital during the air-raid on Thursday the 20th ultimo. Mr Larks said that he could not speak too highly of the work done during the air-raid by all persons concerned. He added that the Police contingent under Inspector Lindsey and Police Sergeant Loram did admirable work, and he felt that the standard of conduct of all the police present was so high that it would be unfair to mention any particular officer.

He appreciated, however, that without the efficient leadership of Inspector Lindsey, assisted by Sergeant Loram, that the operations would not have been so well executed and that the good work done by all the Civil Defence Services represented was due in no small measure to the excellent example and organizing ability of the Police Officers referred to above.”

Letter from Medical Superintendent, Dr Larks: “I should like to take this opportunity to thank you for the considerable service rendered by members of your Force at the City Hospital on the occasion of damage by enemy action on the night of 20th March 1941. They were quickly on the scene, and worked without any consideration for their personal safety under the able control and organization of Inspector Lindsay and Sergeant Loram. Of the other ranks, Constable Down was outstanding.”On 27 March 1941, the coffin-filled grave was shrouded in the red, white and blue of the national flag. On one side were the mourners, and on the other, there was a huge bank of flowers. At one end there were civic and other representatives. The grave will be one of the city’s greatest memorials to two nights of supreme courage. There were many deeply-moving scenes, but the mourners generally bore their sorrow with great fortitude.

Nurses of the children’s ward of a Plymouth hospital are still with their little charges in death. Killed together in the ward when it was devastated by a high-explosive bomb, they were buried in adjoining graves at Efford Cemetery, only a few yards away is the communal grave.

The committal service was conducted by the chaplain of the hospital. Union flags lined the graves, into which relatives and nurses dropped bunches of flowers, violets, roses and daffodils. Afterwards the graves were piled high with spring flowers.

Memories of that night by Joan Rickard, a teenage nursery nurse who off duty with German Measles, on the night that the City Hospital received a direct hit, killing eight nurses and more than 20 children. She had started working as Joan Perry in the hospital’s nursery in September, 1940, when she was 17.“It consisted of unwanted children who had been left at the hospital, most of them since birth. We looked after them until they were three, when they went to a children’s home.

The sick children were in the upstairs ward and the nursery children on the ground floor. There weren’t any shelters but all the ground-floor windows were sandbagged to minimise blast damage.

The children’s ward and nursery received a direct hit and the new maternity block was damaged. Two of the 8 nurses killed were only 16; only three of the 21 nursery children survived this horrific event. Many were killed because when the floor above collapsed, they were trapped in their cots and fire broke out, so making it impossible to rescue them.”

Air Attacks Continue

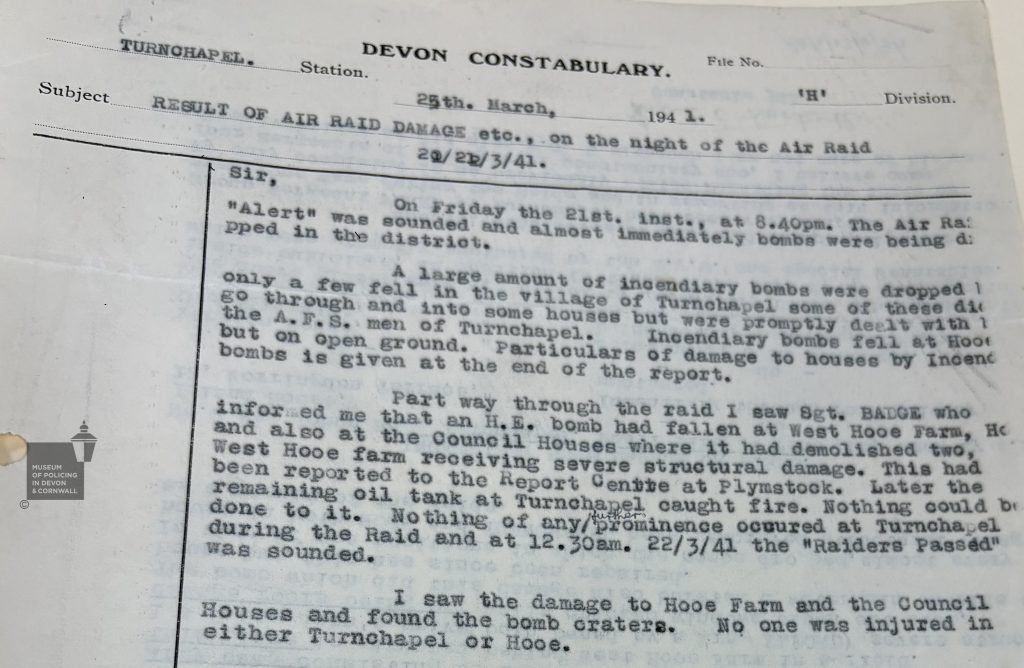

Just outside of Plymouth City Police boundaries, Devon Constabulary were dealing with an air raid just across the Cattewater at Turnchapel on 25th March. The fuel terminals and tanks of the wharves no doubt the targets. Thankfully no-one lost their lives in that particular raid. An excerpt from the police report is shown below:

All of the services involved in the war effort on the home front in Devon and Cornwall during the air raids were regularly dealing with choking smoke, coal gas fumes, rubble dust, fire hoses and water everywhere. People barely able to breathe let alone see, rushing out from safety with stirrup pumps and buckets to put out flaming incendiary devices and save lives.

Cornwall Constabulary towns Saltash and Torpoint were attacked in April. Torpoint being situated just across the water from Devonport dockyard, the town was bound to be a target, the police station was badly damaged but thankfully no one in the building was badly hurt. However, PC Smitheram 126 was badly injured whilst out on patrol.

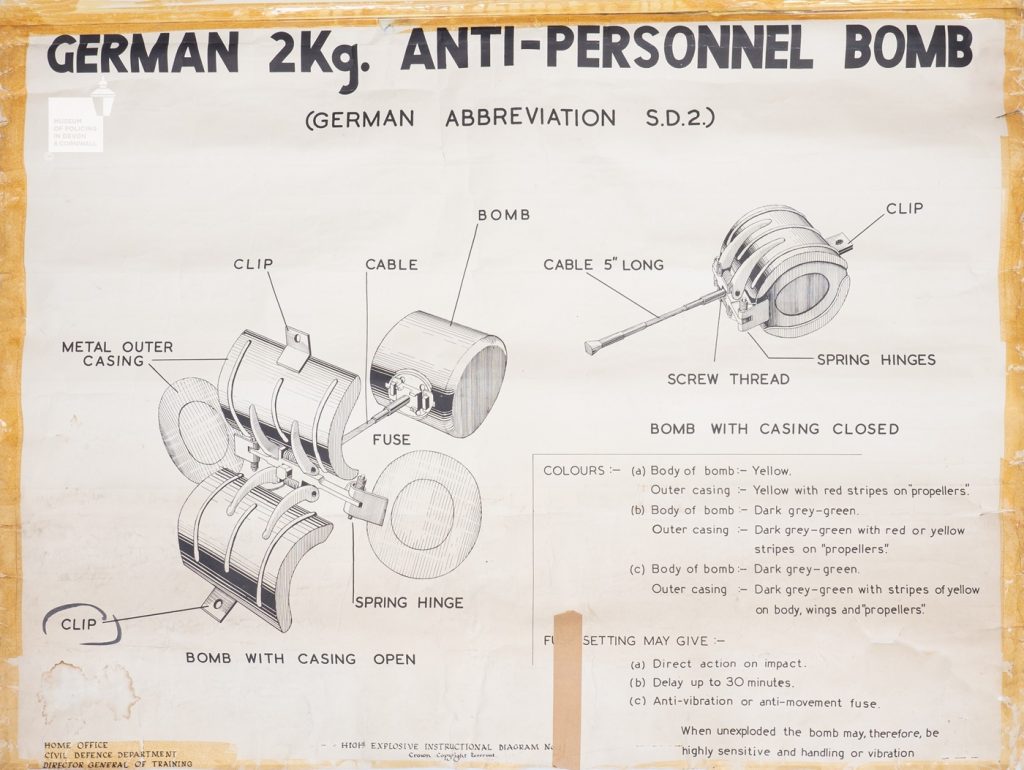

Tragically whilst rendering aid to Plymouth in April 1941, six volunteer firemen of the Saltash Auxiliary Fire Service were killed when their appliance hit an unexploded bomb. Penzance and surrounds were hit by several air raids, the worst attack on 8th June saw dozens of incendiary bombs and ten high explosive (HE) bombs inflicting serious damage (see fig 7 to see an illustration of HE bombs). Nine lives were lost including, we believe, a police sergeant whose name is presently unknown.

Exeter suffered bombing at various periods but not on the scale of Plymouth and its surrounds during 1941.

A major problem of the air raids in Plymouth and Exeter, was the need for speedy information regarding casualties. This responsibility again fell to the Police. As soon as air raid news was broadcast on the wireless (radio) it was down to the police to provide timely updates to all in need of the information. Lists of casualties were posted at various police stations and town halls to do everything possible to keep the public informed.

To aid the reduced and now overstretched regular officers of the police force, the First Police Reserve were recruited comprising retired men used for office work, enquiries and guarding vulnerable points. Police War Reserve were those directed (conscripted) into the service as an alternative to HM Forces along with a big increase in part-time Special Constabulary men.

Plymouth’s Women’s Auxiliary Police Corps (WAPC), increased full and part time numbers covering office work, canteen, driving duties etc.

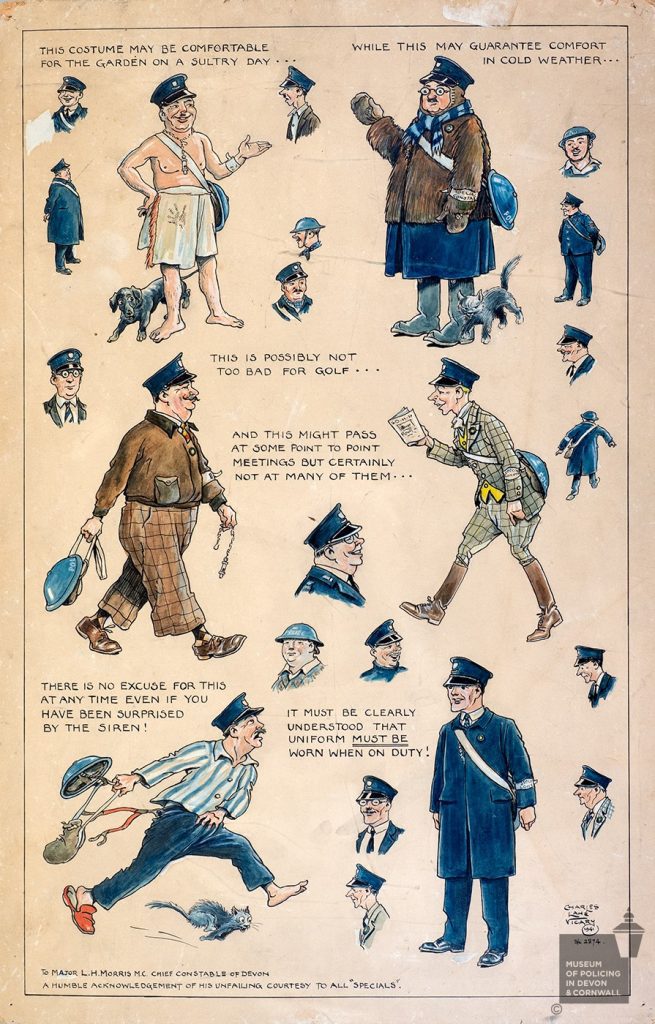

Despite the difficulties of wartime in 1941, a humorous and cheerful original artwork (Fig 8) was created and presented to Devon’s Chief Constable Morris by Special Constable 2874 Charles Lane Vicary of Newton Abbot.

Throughout all these raids, young people of the Police Auxiliary Messenger Service (PAMS) bravely kept on cycling between Control Rooms, collecting and delivering messages. Telephone services were regularly knocked out, and the PAMS were vital in keeping the lines of communications open.

The Trekkers 1941 & 1942

Many people in Plymouth were left homeless by the blitz, with whole areas destroyed or uninhabitable. The authorities set up rest centres in the surrounding areas. However, they were not prepared for the numbers who would leave the city nightly for refuge from the bombs especially after the Portland Square disaster on 22nd April 1941 in which a public air-raid shelter took a direct hit with huge loss of life. Struggling with fear and of finding somewhere to stay after being bombed out of their homes people left the city.

Some families caught buses or people might hitch a lift with passing cars and lorries, but many went on foot to places like Plympton and Roborough Down, they went as far as Ivybridge and Tavistock seeking a safe place to sleep, returning to their vital war work in the city the next morning. The authorities were horrified, not only were they not prepared, but they also considered such actions demonstrated a lack of fortitude, though the local consensus was that morale remained good.

On the 24th of April 1942, after particularly heavy raids the nights before, four rest centres in Horrabridge, each designated to support 50 homeless people, took in over 1100 people, opening up the church and squeezing 200 in the school.

Tavistock had space designated for 350 refugees, but that same night in April 1942 they sheltered over 1250 people. Russell Street School was opened taking in 150, Church Hall opened and took in 150 and Kelly College took in a further 50 people, each of these places were not scheduled to be used at all. The Town Hall took in 300, twice it’s specified capacity and the Junior School which was supposed to hold 200 people ended up helping 600 find a warm, safe place to sleep.

At Roborough Down people pitched tents during the blitz nights, they were told they must make straight orderly lines, however one night a plane strafed the tents causing huge numbers of injuries. Following that terrible event the local PC ’Sid’ Pollard cycled up each night to re-arrange them into a random pattern so as not to attract attention from passing raiders. This action by Constable Pollard probably saved several lives from the strafing of enemy machine guns during that time.

Devonport and its Royal Naval Dockyard was a major target for air raids with terrible damage inflicted. On a cloudless night during April 1941 residential areas were attacked and wrecked. A massive explosion in Boscawen Block at HMS Drake killed dozens of Royal Navy servicemen. Any of the houses still standing nearest the ‘yard were deserted at night due to terrified residents leaving the area and joining the other thousands of ‘Trekkers’ outside of the city.

Crime Doesn’t Stop for War

Whilst Plymouth was being torn apart by the blitz, crime continued and the Chief Constable of Plymouth’s Report for 1941 (published in 1942) states: ‘I have to report that looting became prevalent. Altogether 229 cases were reported on of which 136 were detected. There were 137 offenders of whom 70 were juveniles…. Even the provision of the death sentence has not acted as a deterrent to what is a most revolting offence.’

Devon reported a 50% increase in crime, looting being the main reason in 1941. The police were actively trying to prevent people taking property from bomb damaged buildings. In one instance a detective had to physically prevent a looter running from a premises, in the struggle stolen tobacco fell from the man’s pocket. There were many convictions for looting, with some people receiving prison sentences including ‘hard labour’. Research to date by Dr Todd Gray¹ has not found cases against anyone serving in the police services in the whole of Devon and Cornwall during World War Two.

Murder was rare but the case below shows that it happened.

The Blitzed House Murder Mystery of 1942 is recounted by Anne Corry:

This could have been written by Anthony Horowitz for a Foyle’s War mystery but unlike the T.V. programme this murder remains unsolved. What has immediately become known as the “blitzed house” mystery is engaging the attention of the Plymouth C.I.D. On 14th March 1941 22 Royal Navy Avenue was blitzed. Inside the house were the Beare family and Olive and her son Percy Hearn who were killed and the house remained empty until the body of Wladyslaw Gwaizdzinski (Pictured in Fig 10) was found murdered at this house.

“A Polish chief petty officer, Wladyslaw Gwaizdzinski, 40, was found dead in an empty blitzed house. He had received severe head injuries, and foul play was suspected. But for the fact that the window of the ground floor room, in which he was found lying, was facing on to the main road and was partly open, the tragedy might not have been discovered for some time. The house is one of many rendered uninhabitable after the intensive raids earlier in the year. It was patched up to the extent that the windows were filled in and the door replaced, but internally it was not fit for habitation. The walls and ceilings were in a bad state of repair.

This was the scene for the first big mystery since Mr W.T. Hutchings assumed his new office as Chief Constable, but because of his long association with the C.I.D. department and his intimate knowledge of the district, he was at once able to direct inquiries with Chief Inspector Cheffers, of the C.I.D. in charge of the investigation.

At 9.15 a.m. on Thursday a British sailor discovered the tragedy as he was passing along the pavement he glanced in at the half-open window and saw Wladyslaw stretched out on the floor. He was immediately interested, and a more intensive look made him realize that the man was dead. He instantly informed the police who were soon on the scene.

Wladyslaw Gwaizdzinski was found lying on the floor with his head a mass of blood, and resting almost on a heavy stone, which was also covered in blood. From the state of the body and the fact that it was still slightly warm it was obvious that the tragedy had occurred some time during the night or early morning. He was fully dressed in his uniform, even to his respirator, which was still slung over his shoulder and was partly under his body.

The room was in a state of disrepair and contained only a quantity of newspapers and a few bottles. There were serious injuries to the head, but whether the stone lying by the body had been used for an attack is not clear. Plymouth C.I.D. took charge with the Chief Constable visiting the scene. A careful inspection of the body and surroundings was made, as well as a search for any traces of fingerprints on papers and bottles.

His body was removed to the mortuary, and Dr Eric Wordley, city pathologist said after a post-mortem examination found death was due to cerebral haemorrhage and a fractured skull caused by blows on the head from extraneous violence from some object. The victim was a thick-set powerfully-built man. One of the features of the case is the lack of anything that would indicate any violent struggle. The police are particularly anxious to trace any people with whom the victim might have associated during the previous night, and are seeking the identity of a woman in whose company he is understood to have been about midnight.”

In December the police said they were still steadily gathering up the many threads, their chief concern being with the movements of the victim the night before the body was found and interviewing those who had been with him which was proving difficult because they needed an interpreter. Later they specified that a new line of inquiry, which could not be disclosed, promised a definite step to unravelling the mystery. “We are hopeful that some solution will be reached before many days.”

Wladyslaw Gwaizdzinski’s coffin over which the Polish flag was a shroud, was borne on a gun-carriage drawn by a party of British bluejackets, and the British Navy also provided a firing party and bugler. The first part of the service was at the Church of the Holy Redeemer at Keyham, and interment at the Weston Mill Cemetery, a small mound in the Catholic burial ground which will be “forever Poland.” The cortege was led by 8 petty officers of the Polish Navy bearing four large wreaths, three being from deceased’s shipmates and one from the Royal Naval Barracks. Inscriptions on the wreaths, in elaborate letters of gold and silver, were on long ribbons of the Polish colours. After the service these were removed, and will be sent, together with photographs of the burial, to Gwaizdzinski’s widow who is still in Poland.

On Saturday 28 March 1942, Western Morning News, wrote, “There was a further step in the blitzed house mystery, when Mr W.E.J. Major, Plymouth City Coroner, who said with a jury, expressed the opinion that the death of 40-years-old Wladyslaw Gwaizdzinski on 28 March 1942 was a perfectly straightforward case of someone being murdered. “I don’t think this Polish sailor could have got his injuries in any other way.” Considering the possibility of manslaughter, Mr Major thought it reasonable to expect someone would have come forward, but no one had.

Chief Detective Inspector L.M. Cheffers said inquiries made by the police to this date had failed to produce information which would enable the identity of the person responsible for Gwaizdzinski’s death being established. Inquiries were continuing. The jury returned a verdict that Wladyslaw Gwaizdzinski was “Murdered by some person or persons unknown.”

The Prime Minister’s Visit

Rumours abounded that Prime Minister, Winston Churchill would visit Plymouth, however, Chief Constable Lowe refused to give journalists any details and Mr Churchill did visit on 2nd May 1941 (Fig 11). As with all visiting dignitaries it fell to the police to provide the security.

After the Prime Minister’s visit Sir John Colville (a member of the secretariat) wrote that the Prime Minister was deeply moved by what he saw in Plymouth, repeatedly saying ‘I’ve never seen the like.’ (Figs 12 & 13)

National Service Act 1941

Guarding of bombsites and vulnerable areas was becoming increasingly difficult, people could no longer recognise their streets, where were their wrecked homes? Everyone involved in helping the war effort were exhausted. The military police assisted with directing traffic and helping residents in Devonport whilst the Navy assisted with bomb damage clearance, but more help was needed.

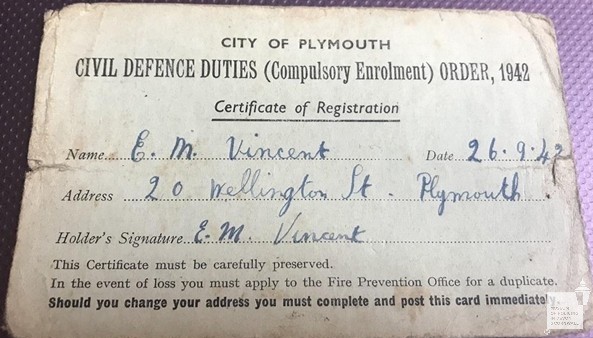

In December 1941 a second National Service Act was passed by the government, this extended the upper age limit for men to 51 years, it also required unmarried women aged under 31 years to register with the Ministry of Labour for National Service. One section of the Act dealt with conscientious objectors by declaring that there could be ‘no objection’ to deployment in civil defence which included the police service.

Air raids in Devon 1942

24th to 25th April 1942 saw bombing at Newton Abbot, one of which killed Special Constable Frederick Pearse and Area Officer Samuel Chetham who were on patrol. The two men were trying to shelter from the blast but were hit by flying debris.

The Baedeker Raids in Exeter

It is thought that reprisals for the bombing of Lübeck and other historic towns in Germany brought about the Baedeker air raids. Targets for enemy air attacks were historic cities and Exeter was first on the raid list. The worst raid took place overnight on 3rd and 4th May on 1942, at dawn the city was on fire and collapsed buildings hampered all access. Much of Paris Steet lay in ruins and people were in a state of shock picking their way through the rubble of Sidwell Street and High Street.

Mutual aid was given by Plymouth City Police to Exeter City Police at this time. Helping with rescues, firefighting, guarding vulnerable buildings and keeping lines of communications open to distressed people.

Tragically, Exeter City Special Constable Harold Luxton was killed on the 4th May 1942 after being hit by the effects of an air bomb in Sidwell Street as he responded to the air raid alarm.

Air Raid Warden Ernest Howard and Special Constable Victor Hutchings showed immense bravery in rescuing five people from certain death in a gas filled cellar in Verney Street. For their outstanding courage they were both awarded the George Medal. James Henry Reynolds, who was a Police Messenger, about 15 years old, was involved in that same rescue and was later awarded the Kings Medal for Gallantry.

More Help Needed

From 1942 the Home Office were continually demanding Chief Constables release policemen for enlistment in HM Forces. On 24th. May, the Chief Constable of Cornwall Constabulary was told to release 72 of his youngest men for military duty. To meet such demands, he invariably nominated War Reserve PC’s to be released to the armed forces. Exeter City had 40, Devon had 100, Cornwall had 85, whilst Plymouth had 281. The personnel records for Devon and Exeter no longer exist but the Cornish and Plymouth records indicate that some of the War Reserve members had been conscripted into the police service by the Ministry of Labour. Further enrolment orders were made to ensure all eligible people registered for civil defence and again this might have included police duties. In Plymouth the number of WAPC positions had also increased that year, to 50, and an information bureau had been set up to deal with the number of missing person enquiries resulting from air raids. 3,000 communications regarding missing people were dealt with and in nearly every case the required information was obtained. In the same year, the Chief Constable sought to ensure as many police personnel were qualified in First Aid, to respond to the growing human costs of enemy action across the city.

Slapton Raid

An air raid at Slapton on 11th October 1942 killed Special Constable Harry Whittaker and fifteen days later Special Constable John Cartwright DSO, a veteran of World War One was killed in a raid on Seaton. The enemy was now targeting civilians in ‘tip and run’ raids.

Murders in Cornwall

A Falmouth tobacconist, Albert Bateman was found dead on Christmas Eve 1942. His worried wife had reported to police that he hadn’t come home from work as usual. Upon entering the shop, police found Mr Bateman’s body and a murder investigation began. The perpetrator was arrested, put to trial and found guilty. We will cover how this crime was solved, and the circumstances around the murder of WAAF Corporal Joan Lewis in future blog posts.

Last Air raid in Exeter

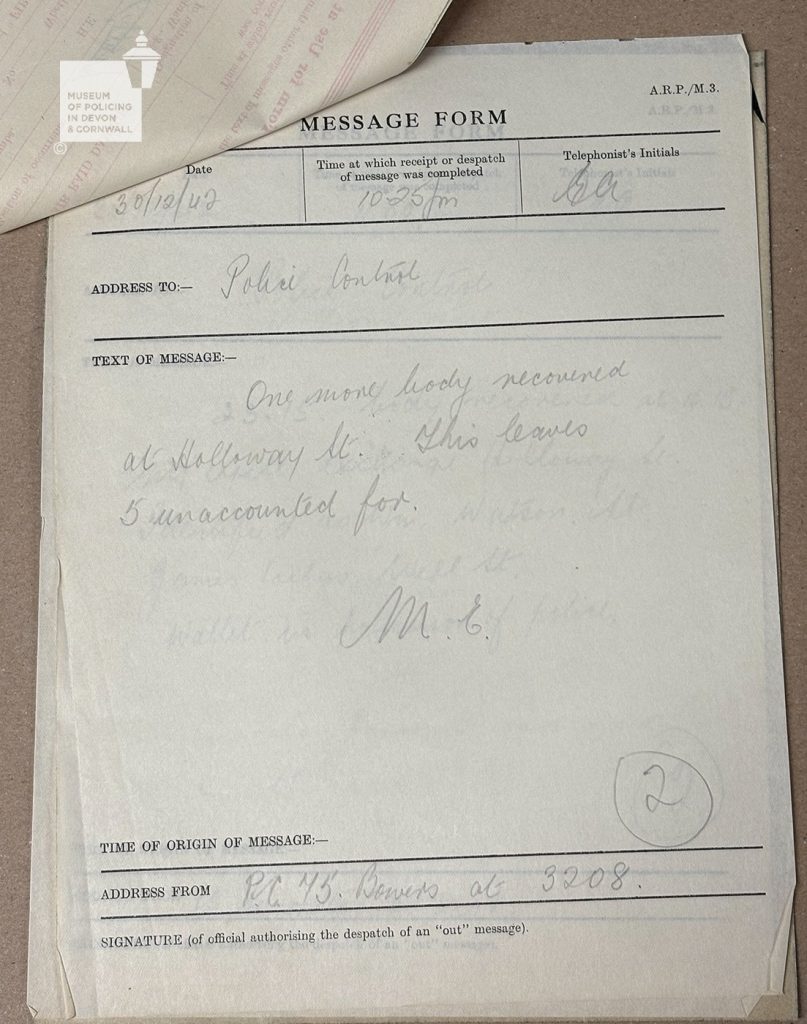

On 30th December 1942, Exeter received a final air raid. Nineteen lives in total were lost with Holloway Street alone suffering twelve fatalities. Hurried pencil written messages (Fig 17) were recorded at police emergency control centres; their matter-of-fact language belies the trauma that the people of these services went through.

On the ‘Exeter Memories’ website Sergeant Collins described what happened when a bomb was dropped on Topsham Road.

‘The bomb passed through the back bedroom window of 95 Briar Crescent, through the floor, into the front room, passing over a settee on which the woman was feeding the baby, then out through the front wall striking the garden footpath, it glanced up ward and removed the roof of 34 Laburnum Road. The bomb then fell into the garden of number 32, still unexploded.’

We can only imagine the faces of those witnessing this event at Briar Crescent and Laburnum Road. The shock and later relief at realising that somehow, they had cheated death.

Some of the worst jobs undertaken by the police was the identification of the dead. Criminal Investigation Departments (CID) were involved in taking witness statements to ascertain possible whereabouts of missing people or attempting to find out the identity of unknown bomb victims. A truly grim task for all of the services involved, but carried out with utmost respect for the dead, and consideration for the distressed and anxious families awaiting news.

The ‘Tip and Runs’ in Devon of 1943

Special Constable Alfred Ford and Special Sergeant William Rendell lost their lives in Kingsbridge and Teignmouth during January. SC Ford’s children were also killed along with two other people in a nearby shop. Special Constable Ronald Hockin died in February along with fourteen others and the last Devon police casualty was Special Constable Francis Allin, killed on duty in Plympton in June.

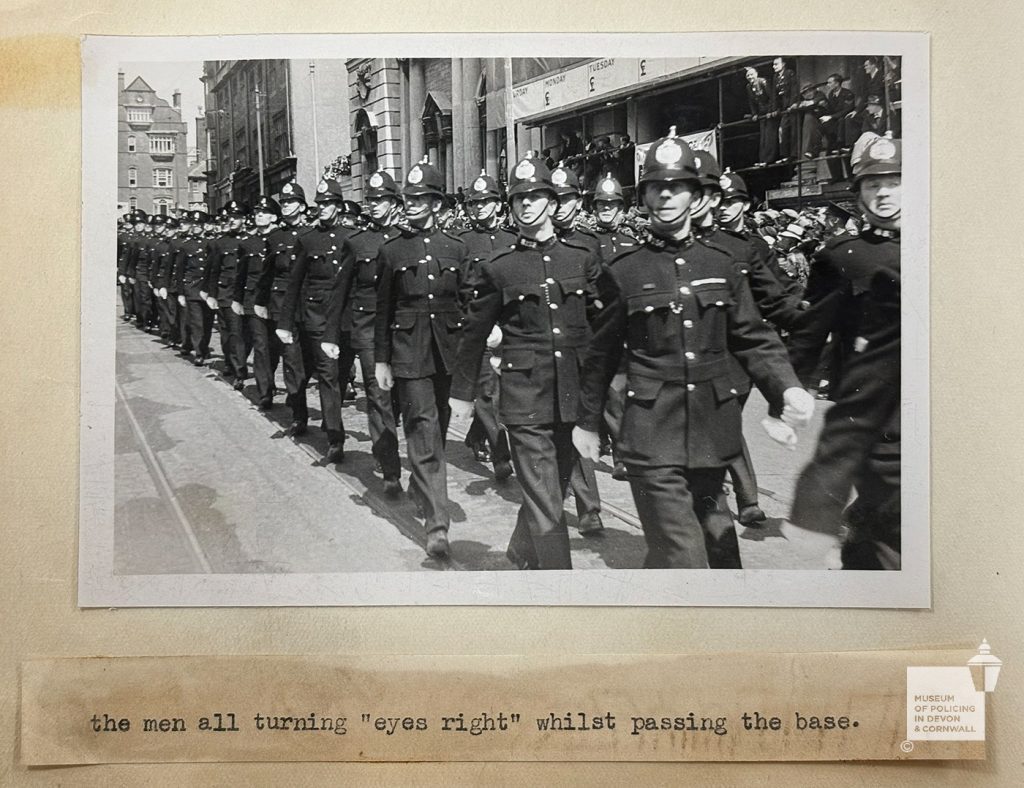

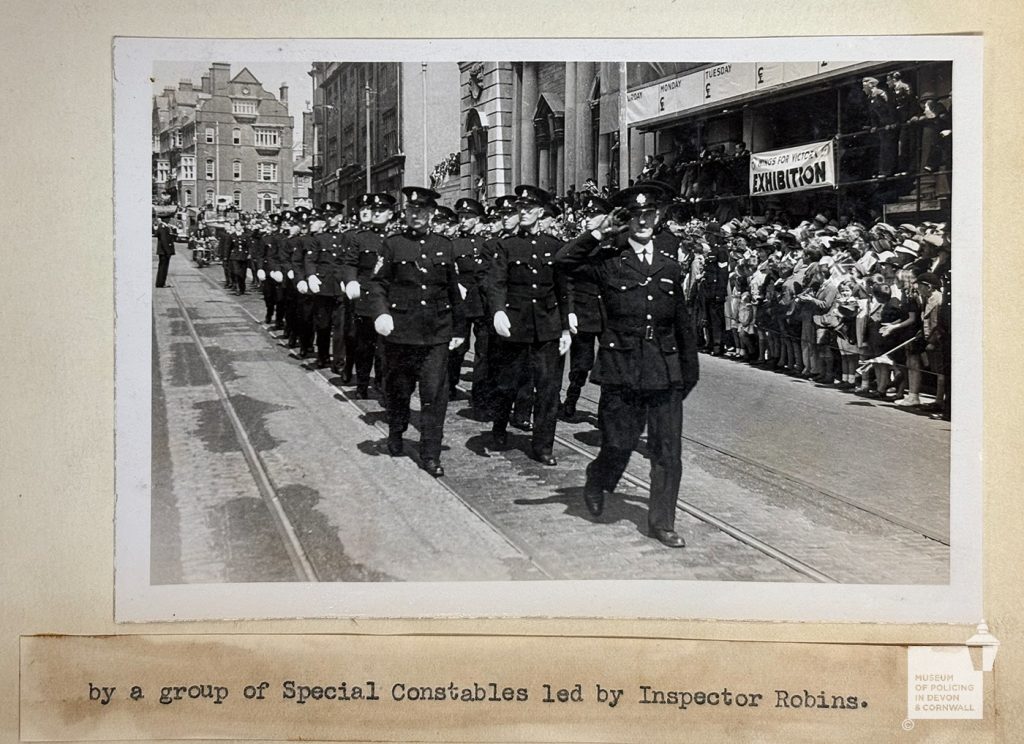

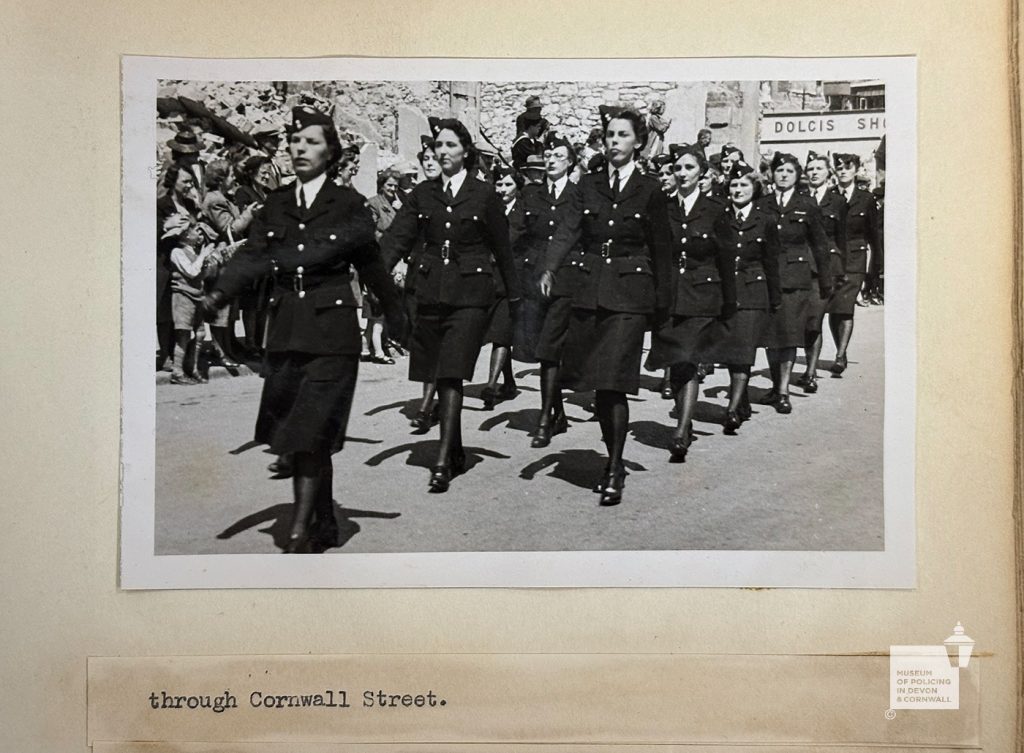

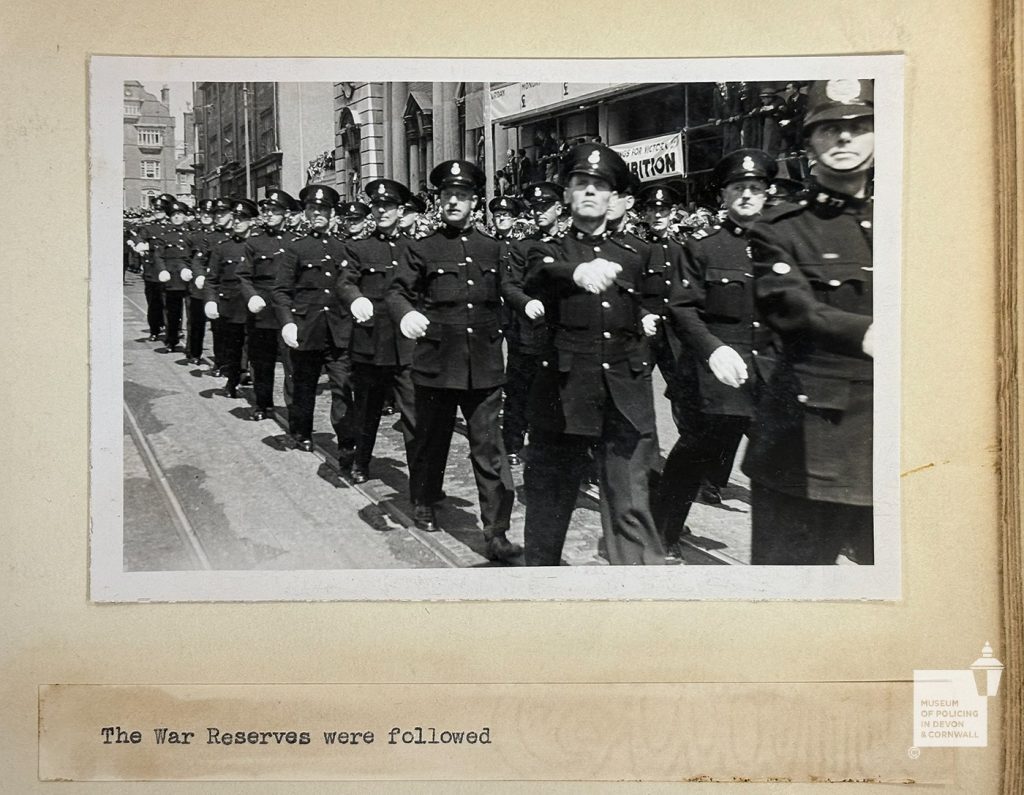

Wings for Victory

National Wings for Victory Week ran in Plymouth from 30th May to 5th June 1943. This was a national effort to raise funds for aircraft building; the government encouraged the public to purchase savings bonds for the war effort. A huge parade of services including the Police (Figs 18, 19, 20, 21) were involved raising nearly £900,000 which equates to £35.6 million today! We found these photographs in a Plymouth City Police photograph album stored in our archive.

Winifred Hooper (WAPC)

Plymouth City Centre and Greenbank stations were both damaged by the air raids of June 1943. Temporary stations were set up at the courts in Princess Street. In his unpublished book ‘From Rattles to Radios’, Ernest Dickaty (formerly Chief Superintendent of Devon & Cornwall Constabulary and of Plymouth City Police) recorded the experience of Winifred Hooper (WAPC) on the night of 11th June when Greenbank was hit: ‘Every night three WAPC’s slept in to be ready to help in the Control Room should there be an air raid. Things had quietened down for some time, we had allowed ourselves the luxury of going to bed in our night attire. That was a big mistake! We awoke to the wailing of the air raid siren, we tumbled out of bed, threw on a few top garments as on many times past the ‘all clear’ would sound as soon we reached the Control Room. As we descended the steps there was the most frightening screaming and whistling which sounded as if it was aiming for my head, then a loud thud and nothing more. Everyone was rooted to the spot. Then I remember Sergeant Kenneth Wherly giving me a steel helmet to put on. Inspector Denley calmly announced that there was an unexploded bomb just above us. Then the order came to evacuate the building, as we left, I think every telephone in the Control Room started to ring. It seemed terrible not being able to answer them.’

We believe that Winifred Hooper can be seen in the photo (Fig 20), on the left behind Eileen Milo.

George Medal Awarded

In further information from his unpublished book From Rattles to Radios, Ernest Dickaty records the following:

‘The Times’ reported on November 20th 1943, ‘The King has approved the following award:

GEORGE MEDAL

Richard Joseph Smale Willis, Police Constable, Plymouth City Police.

(12th August 1943) A high explosive bomb caused considerable damage to a building, PC Willis immediately searched for fire watchers known to be on the premises. One man was quickly located. PC Willis then climbed up to the first floor of the next house and saw an arm sticking out of the debris of the demolished building. The gap, 8ft wide between the houses, was bridged by planks and Willis crossed to find a seriously injured man. After working for an hour in a confined space the victim was released. A few moments after the injured man had been removed the building collapsed and several tons of masonry fell on the spot where PC Willis had been working.

The Slapton Evacuation

In November 1943 Devon County Council were ordered by the War Cabinet to completely evacuate the residents of 30,000 acres of land in and around Slapton Sands (nr. Kingsbridge). The South Hams villages of Torcross, Slapton, Strete, Blackawton, East Allington, Sherford, Stokenham and Chillington were affected. All men, women and children were ordered to leave within 6 weeks, the residents co-operated without fuss and the evacuation was completed on 20th December. We assumed that the police in the affected villages would have received instructions to assist, but due to the top-secret nature of the evacuation we have not found any documents in our archive. We know that the local police stations closed down, and the area was deserted as of 21st of December 1943.

1944

American troops moved into the evacuated South Hams areas for training.

The final air raids in Plymouth happened in March and April, thankfully without any reported loss of life. Cornwall Constabulary were given approval to begin appointing up to twenty attested policewomen in this year. However, we have not found any appointment details in the archives, perhaps recruitment was shelved due to the arrival of American servicemen training for the Battle of Normandy 1944.

Operation Overlord

Thousands of troops from the USA had been billeted in Devon and Cornwall as they trained for Operation Overlord, the codename for the Battle of Normandy and usually known today as the D-Day Landings of 1944. Movement of troops to and from camps and training areas fell to the police who ensured this was done efficiently. Signposts had been removed earlier in wartime to confuse the enemy should they invade, and once the soldiers were mobilised the police were on hand to direct the troop carriers successfully to their embarkation points. Mutual aid from Lancashire Constabulary was needed in Cornwall for fear of large-scale air raids which, thankfully, did not happen. The Lancashire contingent returned home in June 1944; each man was given a very large Cornish pasty to take back with him!

On 3rd June Major Hare, Chief Constable of Cornwall Constabulary and Lt. Colonel Tangye OBE, DL, Commandant of the Special Constabulary of Cornwall were congratulated for their assistance to the military by the acting Inspector of Constabulary. Sadly, on 12th June Colonel Tangye died, he was a man totally dedicated to his ‘Specials’, ensuring an efficient force and knew most, if not all of his men personally.

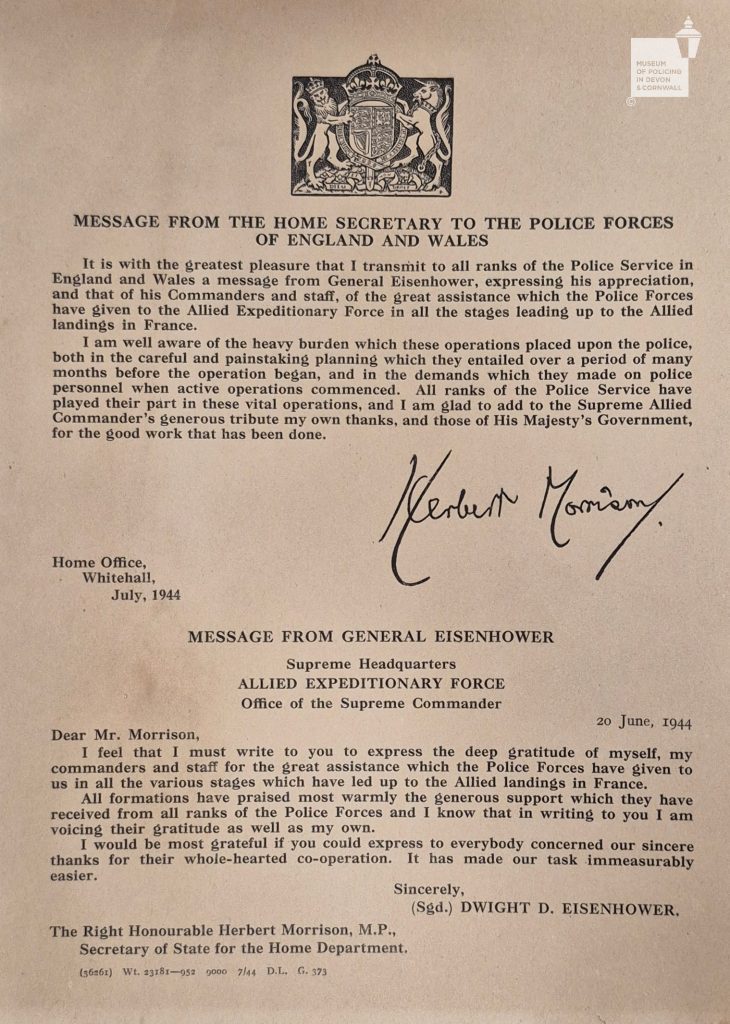

Messages from The Home Secretary & General Eisenhower

In July 1944 messages of thanks were sent to all Police Forces in England & Wales (See Fig 23 above) for their assistance in the lead up to the allied landings:

Here is where we can bring Part 2 to a close.

The lead up to VE Day itself is already on the website blog. The research on that event prompted our recent exhibition and our supporting blog articles. You can read the Ve Day 80 article here: Policing the Home Front – Devon and Cornwall Policing Museum

There will be a final article which will cover the wartime statistics in Devon and Cornwall (where we have them), including a list of police bravery awards and memorials.

With thanks to the following who helped inform this article: Peter Hinchliffe, Mark Rothwell, Andrew Veal-Cox, Simon Dell MBE QCB, Edward Trist, Walter Hutchings, Anne Corry, Gerald Wasley, Alison Holmes, Philip Hutchings, Roy Jewell, Ernest Dickaty, Dr Todd Gray, Miranda Stevens, Imperial War Museum, BBC – WW2 People’s War and Exeter Memories.

- Book Source: Looting in Wartime Britain by Todd Gray. 2009 ISBN 978-1090356-58-6

More about the Saltash Firemen: Saltash OCS Supporting New Tribute To Firemen Killed in WW2 – Kernow Goth

More about the Exeter Blitz: Exeter Memories – The story of the Exeter Blitz, May 1942

More about the South Hams Evacuation: BBC – WW2 People’s War – The Evacuation of the South Hams by Jane Putt.